Atlantis: From Legend To Discovery

by Andrew Tomas

by Andrew Tomas

The Timaeus and Critias of Plato contain a chronicle of Atlantis. The story comes from Solon,  the lawgiver of ancient Greece, who traveled to Egypt about 560 B.C.

the lawgiver of ancient Greece, who traveled to Egypt about 560 B.C.

The hieratic college of the goddess Neith of Sais, protectress of learning, confided to Solon that its archives were thousands of years old. These records spoke of a continent beyond the pillars of Hercules which sank about 9560 B.C.

Plato does not confuse Atlantis with America, as he distinctly says that there was a continent west of Atlantis. He speaks of an ocean beyond the Straits of Gibraltar and calls the Mediterranean “only a harbor”. It is in that ocean-the Atlantic-that he places an island-continent larger than Libya and Asia Minor put together.

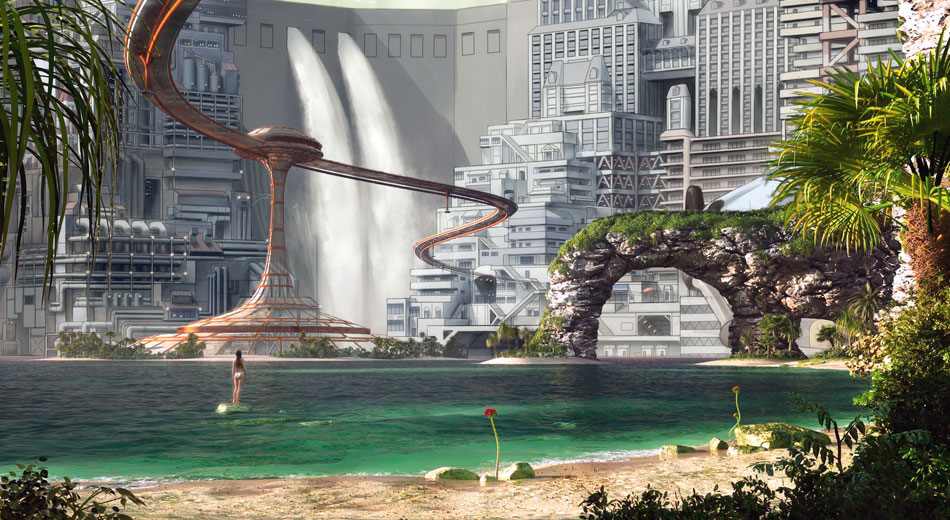

There was a fertile plain in the center of Atlantis protected by lofty mountains from the northern winds. The climate was subtropical and Atlanteans gathered tow crops a year. The country was rich in minerals, metals and agricultural produce. Industry, crafts and sciences flourished in Atlantis. It was proud of many fine harbors, docks and canals. Plato’s mention of commercial links with the outside world indicates the use of ocean-going ships.

The people of Atlantis constructed their buildings of red, white and black stone. The temple of Cleito and Poseidon was surrounded by a golden fence, while the walls were made of silver and the building decorated with golden ornaments. It was there that the ten kings of Atlantis held their assemblies.

On the basis of Plato’s data, the army and navy totaled 1,210,000 men. This figure suggests a multi-million population. During the last period of Atlantean history of which Plato speaks, the nation was ruled by the royal descendants of Poseidon. Shortly before its end, the Atlantean empire entered on a path of imperialism with the intention of expanding its colonies in the Mediterranean.

However, it appear from the account of Plato that in an earlier epoch the Atlanteans practiced gentleness and wisdom. To quote him, “they despised everything but virtue”, they thought “lightly on the possession of gold and other property, which seemed a burden to them; neither were they intoxicated by luxury; nor did wealth deprive them of their self-control”. The people of Atlantis prized fellowship and friendship above their worldly possessions. In the face of this contempt for private property and the sociality of Atlanteans, did they have a system of socialism in a bygone age? If so, the presence of a moneyless economy in the land of the Incas would be only natural, as Peru was, in all likelihood, a fragment of the Atlantean state.

According to Virgil’s Georgics and Tibullus’s Elegies, land in ancient times was held in common. Memories of a democracy in a former cycle were perpetuated in ancient Greece and Rome in the festivals of the Cronia and Saturnalia when masters and slaves drank and danced together for a day. The 5,000-year-old Engidu and the poem of Uttu of Sumer express lament for the lost social system in which “there were no liars, no sickness, nor old age”.

Plato tells of the moral downfall of Atlanteans when avarice and egoism got the upper hand. Then Zeus “perceiving that an honourable race was in a most wretched state” and that they “aggressed wantonly against the whole Europe and Asia”, inflicted a terrible punishment on them. In the words of the Greek philosopher “the warlike men in a body sank into the earth and the island of Atlantis in like manner disappeared and was sunk beneath the sea”.

Anticipating scepticism from his readers in future ages, Plato assures us that his story is “strange, yet perfectly true”. Today his narrative is receiving more and more corroboration from science.

Read more here (full pdf download) Atlantis: From Legend To Discovery.

Posted in True History of Manwith comments disabled.