How Martin Luther Started A Religious Revolution

By Josep Orta

By Josep Orta

Five hundred years ago, a humble German friar challenged the Catholic church, sparked the Reformation, and plunged Europe into centuries of religious strife.

Some say that the beginnings of the Reformation can be traced back to a thunderstorm in 1505. After surviving the tempest, a promising law student at the University of Erfurt in Germany changed the course of his life. The young scholar’s name was Martin Luther, and the foul weather set him on a collision course with Rome and would trigger a crisis of faith in Western Christianity.

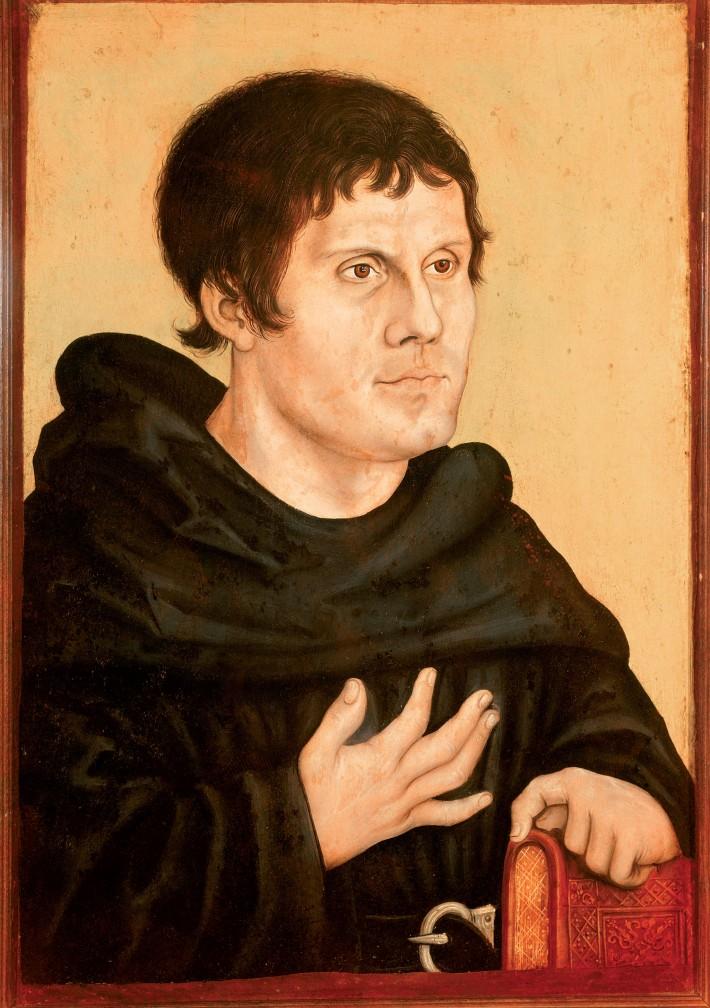

“Portrait of Martin Luther as a Young Man” by Lucas Cranach the Elder depicts the Protestant founder as a simple, sincere monk.

“Portrait of Martin Luther as a Young Man” by Lucas Cranach the Elder depicts the Protestant founder as a simple, sincere monk.

Luther came from a well-heeled family in the central region of Saxony. Luther was born in Eisleben in November 1483. Shortly after his birth, the family moved about 10 miles away to the town of Mansfeld. A successful businessman in copper mining and refining, his father, Hans, had young Martin educated at a local Latin school and later at schools in Magdeburg and Eisenach. In 1501, at age 19, he enrolled in the University of Erfurt to continue his studies.

In 1505 he was returning to Erfurt after visiting his parents when a violent thunderstorm arose with raging winds and driving rain. “[I was] besieged by the terror and agony of sudden death,” the young Luther later recalled. In his panic he made a terror-stricken vow to St. Anne. He would join a religious order, he promised, if only she would save his life.

Biographies of the founder of the Protestant Reformation point out that a deep sense of religious turmoil probably shaped Luther’s thoughts long before the storm. Even so, following his safe deliverance from the tempest, Luther kept his promise and, to the dismay of his father, abandoned his legal education to join the strictly observant Augustinian monastery in Erfurt. It was a decisive, stubborn act, mixed with a deep sense of religious vocation—an attitude he would display for the rest of his remarkable and turbulent life.

Biographies of the founder of the Protestant Reformation point out that a deep sense of religious turmoil probably shaped Luther’s thoughts long before the storm. Even so, following his safe deliverance from the tempest, Luther kept his promise and, to the dismay of his father, abandoned his legal education to join the strictly observant Augustinian monastery in Erfurt. It was a decisive, stubborn act, mixed with a deep sense of religious vocation—an attitude he would display for the rest of his remarkable and turbulent life.

The engraving above shows Martin Luther writing his protest on the door of Wittenberg’s All Saints’ Church. It is from a 1518 German broadside marking the first anniversary of the Ninety-Five Theses. By then, the image of Luther publicly attacking papal corruption had become a potent 16th-century meme.

A Rising Storm

During his first years at the monastery, Luther did not seem to be especially subversive. He quickly made a name for himself not only with his brilliance as a theologian but also with his meticulous observance of the harsh rules governing life in the monastery; he fasted, prayed, and confessed. Content with just a table and chair in his unheated room, he would rise in the early morning hours to pray matins and lauds. By the fall of 1506 he had gained full admission to the order.

Luther continued his theological education after becoming a monk. In 1507 he was ordained by the Bishop of Brandenburg. In 1508 he taught theology at the newly founded University of Wittenberg, where he also received two bachelor degrees.

The Makings of a Rebel

In late 1510 Luther made his first—and last—visit to Rome. During his stay, the friar followed traditional pilgrimage customs. Among other observances, he climbed the steps of the St. John Lateran Basilica on his knees, reciting the Lord’s Prayer on each step. It is said that during his ascent he was perplexed to find the words of the Apostle Paul coming back to him: “the righteous shall live by faith,” a tenet that would form a central part of his later doctrine. During his stay, Luther found himself unsettled by the corruption and lack of spirituality he saw in Rome. He saw openly corrupt priests who sneered at the rituals of their faith. He later described his visit: “Rome is a harlot . . . The Italians mocked us for being pious monks, for they hold Christians fools. They say six or seven masses in the time it takes me to say one, for they take money for it and I do not.”

After returning to Germany, Luther earned his doctorate in 1512. As a professor, he taught several classes at the University of Wittenberg. The spiritual hollowness he had seen in Rome did not break his faith with the church, but scholars believe it continued to disquiet him.

Nailing a Myth

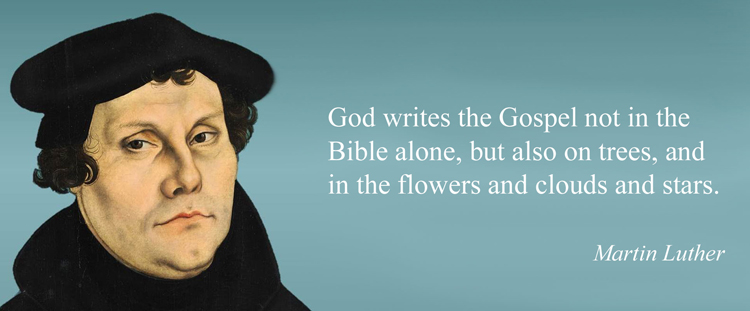

Pages from a printed copy of the Disputation on the Power of Indulgences, better known as the Ninety-Five Theses.

Pages from a printed copy of the Disputation on the Power of Indulgences, better known as the Ninety-Five Theses.

That Martin Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses helped launch the Reformation is beyond question. Dated October 31, 1517, Luther’s letter to his superiors did include copies of the theses. But did he actually nail them to the door of Wittenberg’s All Saints’ Church? The historical consensus is . . . probably not but then again it is possible. Luther himself never mentioned having done so. At the time, he had no idea his theses would create such a stir and would not have seen the need to carry out such a provocative act.

Luther Enters the Fray

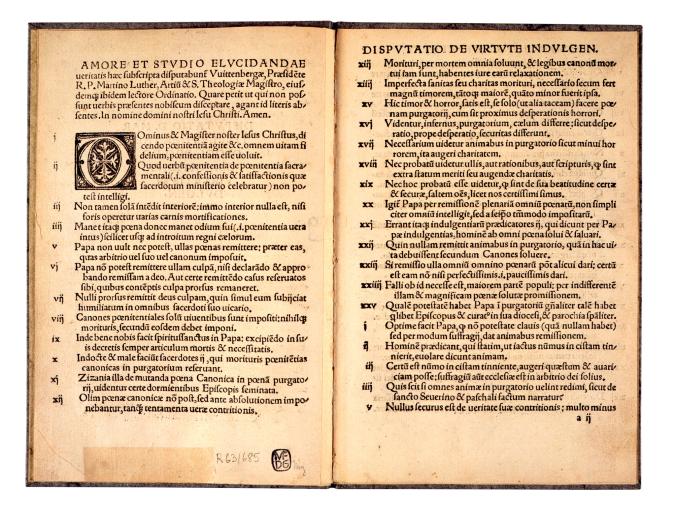

The spark that ignited Luther’s confrontation with Rome was the sale of “indulgences,” which would lessen the impact of, or pardon, a person from their sins. In theory, indulgences were granted by the church on the condition that the recipient carried out some kind of good work or other specified acts of contrition. In practice, indulgences could be bought. The practice was abused by the church, which began relying upon their sale as a way of raising money, especially to pay for costly building projects.

Rome in the early 1500s was under the spell of the artistic projects of the Renaissance. Around 1515, Pope Leo X published a new indulgence in a bid to fund the reconstruction of the Basilica of St. Peter in Rome, entrusting Albert of Brandenburg, the Archbishop of Mainz, with promoting its sale in Germany.

Cameo of Leo X, pope at the time of Luther’s 1517 revolt.

Cameo of Leo X, pope at the time of Luther’s 1517 revolt.

Enraged, Luther took a stand against the papal actions. On October 31, 1517, he composed his Disputation on the Power of Indulgences, better known as the Ninety-Five Theses. According to tradition, he nailed these to the door of All Saints’ Church, Wittenberg, although some modern historians are somewhat skeptical that such a lengthy document could be posted in this way. Regardless of how the Ninety-Five Theses were distributed, many found Luther’s arguments explosive. He argued that the practice of relying on indulgences drew believers away from the one true source of salvation: faith in Christ. God alone had the power to pardon the repentant faithful. The pontifical council ordered him to retract his claims immediately, but Luther refused.

An Elector for an Enclave

Luther’s reformation was not born in a vacuum, and his fate rested as much on the turbulent politics of the day as it did on pure questions of theology. Wittenberg was part of Saxony, a state of the Holy Roman Empire, a patchwork of territories in central Europe with roots deep in the medieval past. The Holy Roman Emperor was appointed by the heads of its main states, influential rulers known as electors.

At the time that Luther wrote his theses, the elector of Saxony was Frederick the Wise. A humanist and a scholar, Frederick had founded the new university at Wittenberg that Luther attended. Frederick’s response to Luther’s theological challenge was complex. He never stopped being a Catholic, but he decided from the outset to protect the rebel friar both from the fury of the church and the Holy Roman Emperor. When in 1518 Luther was summoned to Rome, Frederick intervened on his behalf, ensuring that he would be questioned in Germany, a much safer place for him than Rome. The church was forced to respect Elector Frederick’s wishes because he would be instrumental in choosing the replacement to the ailing Holy Roman Emperor, Maximilian I.

Letters of indulgence, like this one granted in 1512, sparked Luther’s revolt in 1517.

Letters of indulgence, like this one granted in 1512, sparked Luther’s revolt in 1517.

Safe under the wing of Frederick, Luther began to engage in regular public debate on religious reforms. He broadened his arguments, declaring that any church council or even a single believer had the right to challenge the pope, so long as they based their arguments on the Bible. He even dared to argue that the church did not rest on papal foundations but rather on faith in Christ.

Luther must have realized early on that his reform movement had a political dimension. In 1520 he wrote a treatise, “Address to the Christian Nobility of the German Nation.” It argued that all Christians could be priests from the moment of their baptism, that anyone reading the Scripture with faith had the right to interpret it, and that every believer had the right to assemble a free council. This declaration was revolutionary for the ecclesiastic hierarchy of the time.

Heretics and Heroes

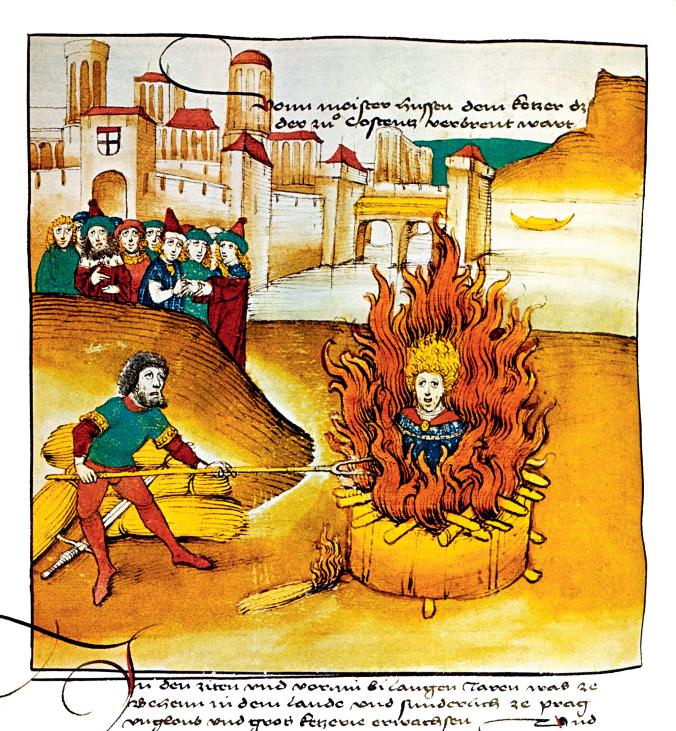

This 15th-century print by Diebold Schilling the Elder depicts the burning of Czech reformist Jan Hus in 1415.

This 15th-century print by Diebold Schilling the Elder depicts the burning of Czech reformist Jan Hus in 1415.

Luther was not the first person to confront the Catholic Church. Writing in the 1370s and ‘80s, Oxford scholar John Wycliffe denounced the wealth of the church, called for a greater emphasis on scripture, and oversaw an English biblical translation. The church condemned Wycliffe, but Oxford University shielded him from arrest. In the 1400s Jan Hus, a scholar at the University of Prague, was exposed to Wycliffe’s works. Hus too believed that scripture was greater than tradition and preached in his native language, Czech. His writings led him to leave Prague for fear of reprisals, but Hus was later arrested in 1414, charged with heresy, and burned at the stake in 1415. Following his death, his followers continued the fight, forming the Hussite movement which spread through what is today the Czech Republic.

Luther in Peril

In January 1521 a papal decree was published under which Luther was declared a heretic and excommunicated. Under normal circumstances, this sentence would have meant a trial and, most likely, execution. But these were no ordinary times. Both Frederick and widespread German public opinion demanded that Luther be given a proper hearing. The newly elected Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, finally acquiesced and called Luther to come before the Imperial Diet (assembly) to be held that spring in the ancient Rhineland city of Worms.

On his journey to Worms Luther was acclaimed almost as a messiah by the citizens of the towns he passed through. On his arrival in Worms in April 1521, crowds gathered to see the man who embodied the struggle against the seemingly all-powerful Catholic Church. Once inside the episcopal palace, Luther was met by young Charles V, princes, imperial electors, and other dignitaries. When charged, Luther said that he stood by every one of his published claims.

The Archbishop of Trier urged him to retract his theses, and Luther asked for time for consideration. After a night of reflection, he remained steadfast. His writings, he maintained, were based on Scripture; on his conscience, he declared he could not recant anything “for to go against conscience is neither right nor safe.” He is said to have concluded with the famous words in German: “Hier stehe ich, ich kann nicht anders—Here I stand, I can do no other.”

The Archbishop of Trier urged him to retract his theses, and Luther asked for time for consideration. After a night of reflection, he remained steadfast. His writings, he maintained, were based on Scripture; on his conscience, he declared he could not recant anything “for to go against conscience is neither right nor safe.” He is said to have concluded with the famous words in German: “Hier stehe ich, ich kann nicht anders—Here I stand, I can do no other.”

Fighting for Faith

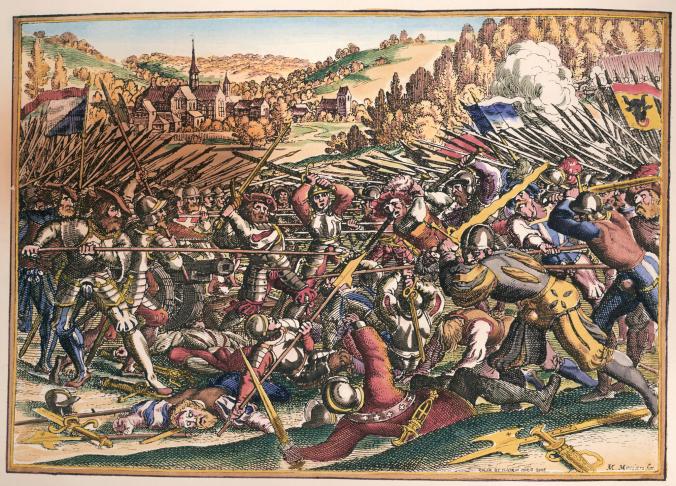

This 17th-century engraving depicts the 1531 Second Battle of Kappel in which Swiss Catholics crushed Zürich Protestants led by Zwingli.

This 17th-century engraving depicts the 1531 Second Battle of Kappel in which Swiss Catholics crushed Zürich Protestants led by Zwingli.

Luther’s revolt inspired other religious leaders in cities outside Germany such as Strasbourg, Geneva, Basel, and Lucca. In Zürich Huldrych Zwingli, a Swiss leader of the Reformation, persuaded the city council and a large part of the population to accept a full program for the strict observance of the Gospel. Priestly celibacy was abolished. Baptism and the Eucharist were still celebrated as sacraments, but the belief that during the Mass the bread and wine actually turned into the body and blood of Christ was abandoned. In Zwingli’s view, the Eucharist became a symbolic rite in remembrance of Christ’s sacrifice. Sacred music was prohibited, and paintings in churches were destroyed. An army of preachers was chosen to go out into the city and foment this radical new teaching.

The Revolution Spreads

Luther left Worms unbowed, but his life was in peril. Charles V signed an edict naming him and his followers political outlaws and demanded their writings be burned. Seized by his protector, Frederick, Luther was granted sanctuary in the castle of Warburg until the situation evolved and the danger passed.

Outlawed for having defended his ideas at the Diet of Worms in 1521, Luther took refuge here in Wartburg Castle, under the protection of Frederick the Wise of Saxony. In this medieval fortress, Luther made his translation of the New Testament into German.

Outlawed for having defended his ideas at the Diet of Worms in 1521, Luther took refuge here in Wartburg Castle, under the protection of Frederick the Wise of Saxony. In this medieval fortress, Luther made his translation of the New Testament into German.

Despite his absence, Luther’s words and writings were spreading like wildfire throughout Germany, thanks in part to the printing revolution. Luther’s declarations at Worms sparked a revolutionary spirit that had been smoldering among the German people, many of who were tired of seeing their earnings gobbled up by the church. Supported by their rulers, also eyeing the opportunity of greater freedom from Rome, a host of reformers came forward in support of Lutheran principles.

Some, to Luther’s dismay, went very much further. Just after Christmas, in 1521, the so-called Zwickau prophets foretold the imminent return of Christ. They wanted to tear down and destroy all religious images, statues, and altarpieces. They even proposed radical changes to the sacraments, the most dramatic of which was their rejection of the rite of baptism for children and a demand that adults be rebaptized. It was from this element that Anabaptism—from the Latin anabaptista, meaning “one who baptizes over again”—grew. Despite savage repression, Anabaptism periodically flared up during the following years.

Another serious threat to the established order was the struggle unleashed by the peasants in 1524 and 1525. The ideas of equality and social justice inherent in Luther’s reform were seized upon by a rural society hungry for change. A revolt erupted across huge swaths of Germany.

Luther may have been a theological radical, but he was not a social reformer. On hearing news of these movements, he voiced his opposition. Having left Wartburg Castle in 1522, he upbraided all Christians who were taking part in insurrections against authority. In an essay entitled “Against the Murderous and Robbing Hordes of the Peasants” (1525), he condemned the peasant violence as work of the devil. He called out for the nobility to track down the rebels like they would rabid dogs as, “nothing can be more poisonous, hurtful and devilish than a rebel.” Without Luther’s backing, the radical revolution was dealt a death blow. In May 1525 the peasants were defeated in Frankenhausen, and their leader was executed.

Rebuilt in the early 1500s on the site of an earlier church, All Saints Church in Wittenberg, Germany, is where Martin Luther was laid to rest in 1546.

Rebuilt in the early 1500s on the site of an earlier church, All Saints Church in Wittenberg, Germany, is where Martin Luther was laid to rest in 1546.

An Unstoppable Force

When the Holy Roman Empire attempted to harden its line against Lutheranism and the wider reform movement at the Diet of Speyer in 1529, the pro-reform German princes dissented, or “protested.” Luther spent the rest of his life consolidating this new “Protestant” movement, whose tenets were spreading across Europe to Strasbourg, Zürich, Geneva, and Basel.

Luther’s efforts created a great rift in Western Christianity and dominated European politics for several centuries as western Europe split into a largely Catholic south and a Protestant north. France straddled the fault line, and for much of the later 16th century was engulfed by religious conflict. The Lutheran doctrine, combined with Tudor power politics, led to England’s ultimate break from Rome in 1534. Years of Catholic-Protestant tensions in England prompted the Pilgrims to embark for the New World in the Mayflower, and laid the foundations for the English Civil War—events that stemmed from the actions of an obscure monk, on an October day exactly five hundred years ago.

Luther’s efforts created a great rift in Western Christianity and dominated European politics for several centuries as western Europe split into a largely Catholic south and a Protestant north. France straddled the fault line, and for much of the later 16th century was engulfed by religious conflict. The Lutheran doctrine, combined with Tudor power politics, led to England’s ultimate break from Rome in 1534. Years of Catholic-Protestant tensions in England prompted the Pilgrims to embark for the New World in the Mayflower, and laid the foundations for the English Civil War—events that stemmed from the actions of an obscure monk, on an October day exactly five hundred years ago.

Historian and author Josep Orta is a specialist in religion in 16th-century Europe

Posted in Other Topicswith comments disabled.