Nuclear War Survival

The Effects Of Nuclear Weapons

The Effects Of Nuclear Weapons

Understanding the major effects of a nuclear detonation can help people better prepare themselves if an attack should occur. When a nuclear weapon is detonated, the main effects produced are intense light (flash), heat, blast, and radiation. The strength of these effects depends on the size and type of the weapon; the weather conditions (sunny or rainy, windy or still); the terrain (flat ground or hilly); and the height of the explosion (high in the air or near the ground). In addition, explosions that are on or close to the ground create large quantities of dangerous radioactive fallout particles. Most of these fall to earth during the first 24 hours.

What Would Happen To People

In a nuclear attack, most people within a few miles of an exploding weapon would be killed or seriously injured by the blast, heat, or initial radiation. People in the lighter damage areas would be endangered both by blast and heat effects. However, millions of people are located away from potential targets. For them, as well as for survivors in the lighter damage areas, radioactive fallout would be the main danger. What would happen to people in a nationwide attack, therefore, would depend primarily on their proximity to a nuclear explosion.

Bomb Types And Yields

The bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki (killing 100 and 60 thousand civilians respectively) were nuclear fission bombs. These split heavy atoms in a chain reaction, releasing energy equivalent to 15,000 – 20,000 tons of the conventional explosive TNT.

In the 1950s, nuclear weapons advanced from fission to fusion. Fusion releases energy by combining light atoms in a chain reaction. Some fusion bombs have yields in the high megaton range, i.e. many thousands of times as powerful (in terms of raw energy released). However, most fusion bombs in today’s arsenals are in the high kiloton or low megaton range, 10-100 times as powerful as the bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

What Is Electromagnetic Pulse?

An additional effect that can be created by a nuclear detonation is called electromagnetic pulse, or EMP. A nuclear weapon exploding just above the earth’s atmosphere could damage electrical and electronic equipment for thousands of miles. (EMP has no direct effect on living things.)

EMP is electrical in nature and is roughly similar to the effects of a nearby lightning stroke on electrical or electronic equipment. However, EMP is stronger, faster, and briefer than lightning. EMP charges are collected by typical conductors of electricity, like cables, antennas, power lines, or buried pipes, etc. Basically, anything electronic that is connected to its power source (except batteries) or to an antenna (except one 30 inches or less) at the time of a high altitude nuclear detonation could be affected. The damage could range from minor interruption of function to actual burnout of components.

Equipment with solid state devices, such as televisions, stereos, and computers, can be protected from EMP by disconnecting them from power lines, telephone lines, or antennas if nuclear attack seems likely. Battery-operated portable radios are not affected by EMP, nor are car radios if the antenna is down. But some cars with electronic ignitions might be disabled by EMP.

You can also protect electronics (portable gadgets such as cell phones, laptops, etc.) from EMP by storing them in a metal pot with a full-metal lid and/or other methods described here.

What Is Fallout?

Nuclear weapons unleash two kinds of hell: first the fire and blast damage – then the radioactive fallout.

When a nuclear weapon explodes on or near the ground, great quantities of pulverized earth and other debris are sucked up into the nuclear cloud. The radioactive gases created by the explosion condense on and into this debris, producing radioactive particles known as fallout.

Fallout emits alpha, beta and gamma radiation. The radioactivity of fallout decreases exponentially over time, eventually rendering it harmless. Because fallout does not emit neutron radiation, it cannot make other things radioactive, except by physical contact.

The amount of fallout would depend on the number and size of weapons and whether they explode near the ground or in the air. There is no way of predicting what areas would be affected by fallout or how soon the particles would fall back to earth at a particular location. Fallout can travel dozens or hundreds of miles from the epicenter of the blast (ground zero) and will not be evenly distributed: especially if the blast occurs during wet weather, fallout will be concentrated into ‘hot spots’ where it will be unusually intense, outside of which it won’t be as bad. The clearer the weather, the farther fallout will travel before it falls, and the weaker it will be when it does.

An area could be affected not only by fallout from a nearby exploding weapon, but also by fallout from a weapon exploded many miles away. Areas close to a nuclear explosion might receive fallout within 15-30 minutes. It might take 5-10 hours or more for the particles to drift down on a community 100 to 200 miles away. No area in the U.S. could be sure of not getting fallout, and it is probable that some fallout particles would be deposited on most of the country.

Because fallout is actually dirt and other debris, the particles range in size. The largest particles are granular, like grains of sand or salt; the smallest are fine and dust-like.

At the time of explosion, all fallout particles are highly radioactive. The larger, heavier particles fall within 24 hours, and they are still very dangerous when they reach the ground. The smaller the particle, the longer it takes to fall. The smallest, dust-like particles may not fall back to earth for perhaps months or years, having lost much of their radioactivity while high in the atmosphere.

Fallout radioactivity can be detected only by special instruments which are already contained in the inventories of many state and local emergency services offices.

Types Of Radiation

Radiation is decaying atoms. Nuclear weapons release four flavors:

ALPHA RADIATION

What it is: naked helium nuclei

Range in air: ~1 inch

Stopped by: outermost layer of skin

Hazards: not super dangerous

BETA RADIATION

What it is: stray electrons

Range in air: ~10 feet

Stopped by: walls, thick stuff

Hazards: internal, external burns

GAMMA RADIATION

What it is: high-energy photons

Range in air: very, very far

Stopped by: nothing completely

Hazards: acute radiation syndrome

NEUTRON RADIATION

What it is: neutrons

Only exists in the immediate time and area of blast.

Only kind of radiation that makes other matter radioactive.

[In order to better understand this, here is a quick explanation by Kim Trinklein, a former physics teacher:

Radiation, as it appears that you are likely to be defining it, is generally considered to be alpha , beta, gamma, and neutron. The only one of these that is energy, not matter, is gamma. Gamma radiation will not make a material radioactive, although there are rare isotopes that can be stimulated to emit a neutron by gamma, but this is almost instantaneous.

Beta is just an electron or positron. Their danger is only the kinetic energy they have, and in the case of the positron, the annihilation energy. Some people object to irradiated meat, even though it was irradiated, to kill bacteria, with beta radiation. The meat cannot be radioactive from high speed electrons. Alpha is basically absorbed like beta minus, with the danger being the kinetic energy. When these types of radiation enter living flesh they can ionize DNA in living cells which can result in a mutation which could lead to cancer, but they do not leave the material radioactive.

Neutrons, however, can be absorbed by a nucleus resulting in an unstable isotope that will then radioactively decay. That’s it.

The other way to make something radioactive is to coat it with a material that is radioactive. If this material is then removed the original material will no longer be radioactive. Source]

Protection From Fallout

For people who are not in areas threatened by blast and fire, but who need protection against fallout, there are three major factors to consider: distance, mass, and time.

A GOLDEN RULE:

Protection from fallout =

[distance from fallout] x

[density of stuff (mass) between you and it] x

[time you’re able to stay put there]

The more DISTANCE between you and the fallout particles, the less radiation you will receive. In addition, you need a MASS of heavy, dense materials between you and the fallout particles. Materials like concrete, bricks, and earth absorb many of the gamma rays. Over TIME, the radioactivity in fallout loses its strength.

The decay of fallout radiation is expressed by the “seven-ten” rule. simply stated, this means that for every seven-fold increase in time after detonation, there is a tenfold decrease in the radiation rate. For example, if the radiation intensity one hour after detonation is 1,000 Roentgens (R) per hour, after seven hours it will have decreased to one-tenth as much – or 100 R per hour. After the next seven-fold passage time (49 hours or approximately two days), the radiation level will have decreased to one-hundredth of the original rate, or be about 10 R per hour.

One way to protect yourself from fallout is by staying in a fallout shelter. The first few days after an attack would be the most dangerous time. How long people should stay in shelter would depend on how much fallout was deposited in their area. In areas receiving fallout, shelter stay times could range from a few days to as much as two weeks, or somewhat longer in limited areas.

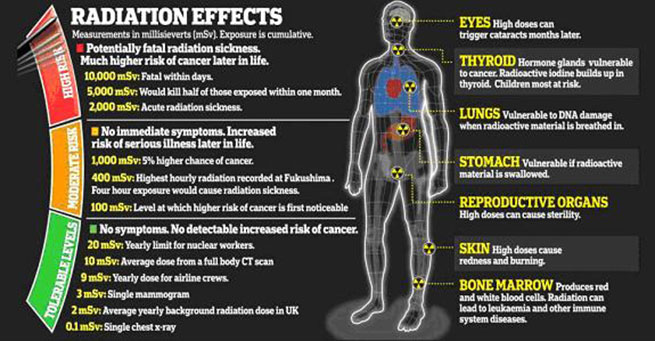

Radiation Sickness

The invisible, radioactive rays given off by fallout particles cause radiation sickness – that is, physical and chemical damage to body cells. A large dose of radiation can cause serious illness or death. A smaller dose (or the same large dose received over a longer period of time) allows the body to repair itself.

Broadly speaking, radiation has a cumulative effect, acting much like a chemical poison. Like chemicals, a large single dose can cause death or severe sickness, depending on its size and the individual’s susceptibility. Usually the effects of a given dose of radiation are more severe in the very young, the elderly, and people not in good health. On the other hand, people can be subjected to small daily doses over extended periods of time without causing serious illness, although there may be delayed consequences. Also, like illness from poison, one person cannot “catch” radiation sickness from another; it’s not contagious.

There are three kinds of radiation given off by fallout: alpha, beta, and gamma. Alpha radiation is stopped by the outer skin layers. Beta radiation is more penetrating and may cause burns if unprotected skin is exposed to fresh fallout particles for a few hours. But of the three, gamma poses the greatest threat to life and is the most difficult to protect against. Gamma radiation can penetrate the entire body – like a strong x-ray – and cause damage in organs, blood, and bones. If exposed to enough gamma radiation, too many cells can be damaged to allow the body to recover.

Following are estimated short-term effects on humans after brief (a period of a few days to a week) whole-body exposure to gamma radiation.

50-200 R exposure. Less than half of the people exposed to this much radiation suffer nausea and vomiting within 24 hours. Later, some people may tire easily, but otherwise there are no further symptoms. Less than 5 percent (1 out of 20) need medical care. Any deaths occurring after this much radiation exposure are probably due to complications arising from other medical problems such as infections and diseases, injuries from blast, or burns.

200-450 R exposure. More than half of the people exposed to 200-450 R in a brief period suffer nausea and vomiting and are ill for a few days. This illness is followed by a period of one to three weeks when there are few if any symptoms – a latent period. Then more than half experience loss of hair, and a moderately severe illness develops, often characterized by a sore throat. Radiation damage to the blood-forming organs results in a loss of white blood cells, increasing the chance of illness from infections. Most of the people in this group need medical care, but more than half will survive without treatment.

450-600 R exposure. Most of the people exposed to 450-600 R suffer severe nausea and vomiting and are very ill for several days. The latent period is shortened to one or two weeks. The main episode of illness that follows is characterized by extensive bleeding from the mouth, throat, and skin, as well as loss of hair. Infections such as sore throat, pneumonia, and enteritis (inflammation of the small intestine) are common. People in this group need extensive medical care and hospitalization to survive. Fewer than half will survive in spite of the best care.

600 to over 1,000 R exposure. All the people in this group begin to suffer severe nausea and vomiting. Without medication, this condition can continue for several days or until death. Death can occur in less than two weeks without the appearance of bleeding or loss of hair. It is unlikely, even with extensive medical care, that many can survive.

Several thousand R exposure. Symptoms of rapidly progressing shock occur immediately after exposure. Death occurs in a few hours to a few days.

Symptoms of radiation sickness may not be noticed for several days. The early symptoms are lack of appetite, nausea, vomiting, fatigue, weakness, and headache. Later, the patient may have a sore mouth, loss of hair, bleeding gums, bleeding under the skin, and diarrhea. Not everyone who has radiation sickness shows all these symptoms, or shows them all at once. Even for people who survive early sickness, any exposure to fallout radiation could have effects that may not appear for months or years.

If There Is A Nuclear Flash

It’s possible that your first warning of an enemy attack might be the flash of a nuclear explosion. Or there may be a flash after a warning has been given and you are on your way to shelter.

The light and heat of a nuclear blast will reach you long before the noise or force. DO NOT look at the light or flash! Keep to whatever shadows you can find.

If you’re close enough to a blast to hear it within 20-30 seconds of seeing it, you will probably just die instantly. Therefore, if you see the light, take shelter ASAP preferably below ground level and assume a 1-2 minute wait before any sound or blast force reaches you. Don’t move from that spot or get caught walking around outside until at least after the shock wave has passed – and expect there may be more blasts.

Travel To Shelter

After the initial blast, you “may” have up to 40 minutes to reach long-term shelter before the first fallout begins to reach you. However, in the event of a large nuclear strike, be warned that more warheads may already be on their way and may also detonate during that time.

If there’s a more ideal shelter within 30 minutes travel time, weigh the benefits of getting there against the risk of exposing yourself to subsequent blasts. If you have a choice, travel by the most sheltered/shady route available.

If your ideal shelter is more than 30 minutes from where you are, don’t even think about it. The first fallout after the blast will be the most dangerous.

Types of Shelters

There are two kinds of shelters – blast and fallout. Depending on its strength, a blast shelter offers some protection against blast pressure, initial radiation, heat, and fire. However, even a blast shelter would not withstand a direct hit. If you live in a likely target area, you should plan to evacuate to a safer place.

If you live in a small town or rural area away from large cities or major military or industrial centers, the chances are you’re not going to be threatened by blast, but by radioactive fallout from an attack. In such a place, a fallout shelter can give you protection.

A fallout shelter is any space that is surrounded by enough shielding material – which is any substance with enough weight and mass to absorb and deflect fallout’s radiation – to protect those inside from the harmful radioactive particles outside. The thicker, heavier, or denser the shielding material is, the more protection it offers.

If you are advised to take shelter, you have two options: go to a nearby public shelter or take the best available shelter in your home.

Public Fallout Shelters

Existing public shelters are fallout shelters; they will not protect you against blast. They are located in larger public buildings and are marked with the standard yellow-and-black fallout shelter sign. Shelter can also be found in some subways, tunnels, basements, or the center, windowless areas of middle floors in high-rise buildings.

NOTE: Unfortunately by the late 1970s, the public fallout shelter program was discontinued in the U.S. by the government.

But recently, crowd-sourced fallout shelter maps have been cropping up online. Check the link here for further information.

Home Fallout Shelters

A basement, or any underground area, is the best place to build a fallout shelter. Basements in some homes are usable as family fallout shelters without major changes, especially if the house has two or more stories and its basement is below ground. If your home basement – or one corner of it – is below ground, build your fallout shelter there.

For more information on how to build a home fallout shelter see examples here:

Fallout Shelters: Protecting Family And Livestock

Alternate Fallout Shelter

GREAT: a big building

GREAT: concrete or brick walls

GREAT: toward the center of the floor

GREAT: below ground level

GREAT: as much distance and density of matter as possible between you and anywhere fallout could accumulate.

OKAY: somewhere you can get to ASAP

BAD: on the top floor

BAD: on the ground floor

BAD: within view of adjacent rooftops

BAD: anywhere exposed to the elements

BAD: anywhere more than 20 minutes away from where you are at the time of the first blast.

EXAMPLES OF GREAT SHELTERS: the center of the bottom of a large, fully enclosed underground parking garage, underneath a supermarket. The basement of a large school or apartment complex.

OKAY SHELTERS: the center-most point of a house basement. The center of the second story of a big 3-story building.

BAD SHELTERS: an attic. The ground floor of a small building. An open-air parking structure. A floor of an office building in line with the rooftops of other nearby buildings.

Identify the best places close to where you live, where you work, or other places you might be. Ideally it should be somewhere you could stay for two straight weeks if you had to. Keep a mental or drawn-out map of these places.

Improving Shelter

If you’re in a house basement or other ‘decent’ shelter, you can significantly improve the radiation protection it offers by before and/or after stacking books, clothes, supplies, anything, up against the inside walls to serve as radiation barriers. Before a nuclear attack, you can improve your shelter by piling up dirt against the outer walls.

Remember since fallout does not emit neutron radiation, any matter you use as a radiation barrier can be safely handled later. You can safely use your food and water supplies as a radiation barrier (as long as they don’t get fallout on them).

(Optionally, if you have a course of potassium iodide pills, start taking them. They mitigate the risk of radiation-induced thyroid cancer later.)

After that, stay put there. Do whatever you can to stay as calm as possible under the circumstances and pass the time.

Waiting Out The Fallout

Fallout decays exponentially and eventually becomes relatively harmless. Conversely, the very first fallout is by far the most dangerous. The sooner it is after an attack, the more crucial it is to stay inside and protected.

If you had no choice but to shelter in a place with no food, water, or something else you need, stay there as long as you can stand to do so before you go out looking for supplies or better shelter.

Every hour you wait, the fallout will become measurably less radioactive.

As explained, this decay follows the seven ten rule: for every factor of seven in time, fallout decays by a factor of ten. Therefore:

– 7 hours after the blast, fallout is 1/10th as radioactive as it was at first.

– 7^2 = 49 hours (2 days) after the blast, fallout is 1/100th as radioactive.

– 7^3 = 343 hours (2 weeks) after the blast, fallout is 1/1,000th as radioactive.

– 7^4 = 2401 hours (100 days) after the blast, it’s down to 1/10,000th

The radioactivity of fallout will never reach absolute zero, but it will eventually become more or less somewhat trivial.

Venturing Outside

There is no gear that can shield against the radiation fallout emits – but you can limit your radiation exposure by:

(A) Being outside for as short a time as possible (if at all), and

(B) Wearing gear that keeps fallout from sticking to you, so that once you go back inside your radiation exposure stops.

A fallout protection suit might therefore look like an emergency rain poncho, rain boots, dish gloves, swim goggles, and a paper dusk mask. Cover your hair with a shower cap. If you have a beard, consider shaving. Anything that might catch fallout particles and hold them close to you is a risk you can minimize.

While outside, move quickly, but don’t stir up dust/ash that might get on you.

Remember you can safely handle anything that has been exposed to fallout so long as it does not have fallout “on” it – up to and including food items. If you were to find a loaf of bread sitting out in the fallout, you could cut off (and safely dispose of) the crust and eat the rest. Any food or water stored in sealed containers, and anything that can be peeled, should be safe to consume.

The more time passes, the more time you can safely spend outside – but when traveling in a potential fallout zone remember that there will be ‘hot spots’: radiation will be more intense in some areas and less so in others.

Unless you have a Geiger counter you’ll have to rely on an outside authority, or pure necessity, to tell you when it’s a good idea be outside without protection. But eventually that time will come.

Re-entering Shelter

Take all possible steps to keep your shelter clean and fallout-free! Take off anything that might have caught fallout particles (i.e. all that gear, and ideally any clothes worn underneath as well) and store them in a sealed plastic bag as far from people as you can. Reuse what you must and discard what you can.

If you have enough clean water to take a shower, do it, with plenty of soap and shampoo – but DO NOT use conditioner! It can bind fallout particles to your hair. (And make sure the waste water from your shower ends up far from people.)

If you can’t take a shower, moist towelettes will do. Gently wipe your eyelids and ears, and blow your nose. Wipe off any exposed skin. Dispose of the towelettes in a sealed plastic bag. Store that bag far from people.

Health Effects Of Radiation

There are two main health hazards from radiation after a nuclear explosion:

(A) Beta burns: similar to sunburns, caused by exposure to fallout at close range / getting it on you.

(B) Acute radiation syndrome: full-body sickness caused by accumulated exposure to gamma radiation at any range.

Avoid beta burns by limiting exposure to fallout. Make sure it doesn’t get on your body, or anything you keep close to you.

Avoid acute radiation syndrome (A.R.S.) by finding the best shelter you can. Keep as much distance and mass between you and fallout as you can, for as long as you can.

If you can’t access medical care, for either beta burns or A.R.S., the best treatment is rest and fluids. Survivors of Hiroshima fared much better if they stayed still for even the first 8 hours after initial exposure to radiation.

The symptoms of A.R.S. include nausea, vomiting, fatigue, and headache – and, in more extreme cases, diarrhea and fever. HOWEVER, note that all of these symptoms can also be caused by extreme stress! If you start having symptoms, reserve judgment. Don’t despair. You are inevitably under a great deal of stress.

Remember that acute radiation syndrome is not contagious, and anyone suffering from it is not radioactive. Help affected people any way you can without fear. And remember that acute radiation syndrome is not necessarily fatal. It is possible to make a complete recovery with time.

GOOD LUCK. BE SAFE.

GOOD LUCK. BE SAFE.

THE WORLD THAT RISES FROM THESE ASHES WILL NEED YOU IN IT.

References used for this article:

D.I.Y Nuclear War Survival: A Quick & Dirty Pocket Guide

FEMA Nuclear War Survival Guide![]()

Household Items That Could Save You in a Nuclear War

Simulate a Nuclear Explosion in Any City

Downloadable PDFs:

Be Prepared For A Nuclear Explosion – FEMA

Fallout Protection: What To Know And Do

In Time Of An Emergency: Nuclear Attack

Posted in Other Topicswith comments disabled.