When we reflect on the vastness of the universe, our humdrum cosmic location, and the inevitable future demise of humanity, our lives can seem utterly insignificant. As we complacently go about our little Earthly affairs, we barely notice the black backdrop of the night sky. Even when we do, we usually see the starry skies as no more than a pleasant twinkling decoration.

When we reflect on the vastness of the universe, our humdrum cosmic location, and the inevitable future demise of humanity, our lives can seem utterly insignificant. As we complacently go about our little Earthly affairs, we barely notice the black backdrop of the night sky. Even when we do, we usually see the starry skies as no more than a pleasant twinkling decoration.

This sense of cosmic insignificance is not uncommon; one of Joseph Conrad’s characters describes

one of those dewy, clear, starry nights, oppressing our spirit, crushing our pride, by the brilliant evidence of the awful loneliness, of the hopeless obscure insignificance of our globe lost in the splendid revelation of a glittering, soulless universe. I hate such skies.

The young Bertrand Russell, a close friend of Conrad, bitterly referred to the Earth as “the petty planet on which our bodies impotently craw.” Russell wrote that:

Brief and powerless is Man’s life; on him and all his race the slow, sure doom falls pitiless and dark. Blind to good and evil, reckless of destruction, omnipotent matter rolls on its relentless way…

This is why Russell thought that, in the absence of God, we must build our lives on “a foundation of unyielding despair.”

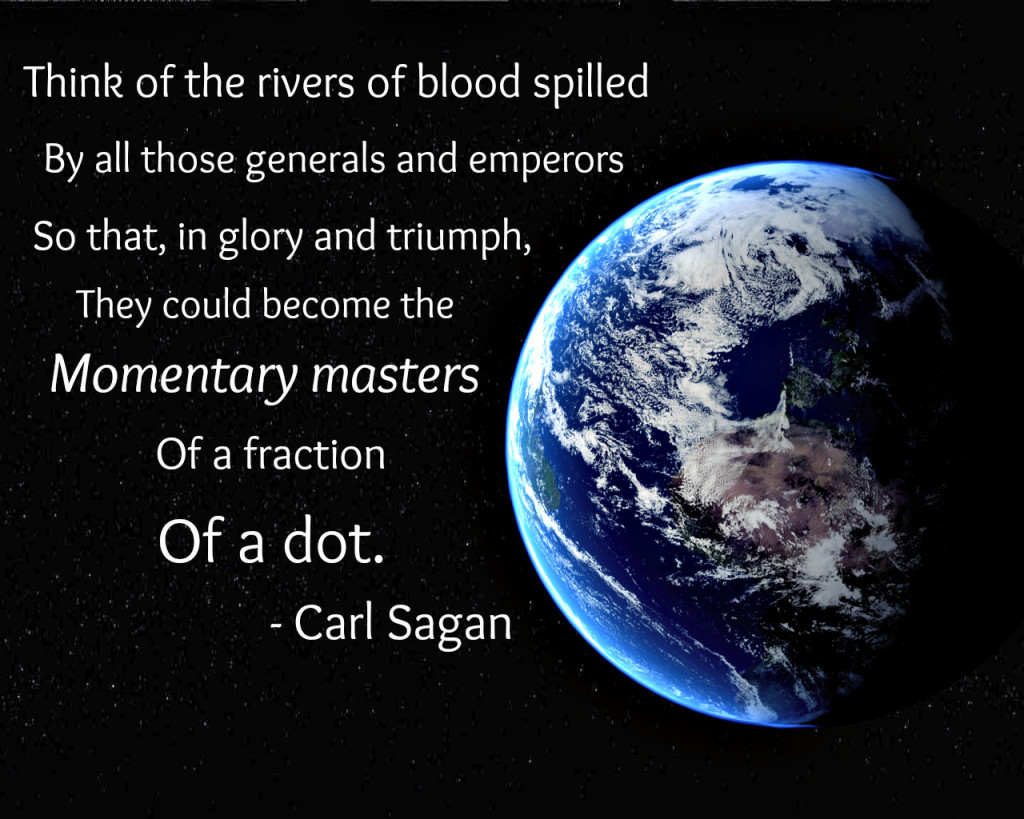

When we consider ourselves as a mere dot in a vast universe, when we consider ourselves in light of everything there is, nothing human seems to matter. Even the worst human tragedy may seem to deserve no cosmic concern. After all, we are fighting for attention with an incredibly vast totality. How could this tiny speck of dust deserve even a fraction of attention, from that universal point of view?

This is the image that is evoked when, for example, Simon Blackburn writes that “to a witness with the whole of space and time in its view, nothing on the human scale will have meaning”.

Such quotations could be easily multiplied—we find similar remarks, for example, in John Donne, Voltaire, Schopenhauer, Byron, Tolstoy, Chesterton, Camus, and, in recent philosophy, in Thomas Nagel, Harry Frankfurt, and Ronald Dworkin.

The bigger the picture we survey, the smaller the part of any point within it, and the less attention it can get… When we try to imagine a viewpoint encompassing the entire universe, humanity and its concerns seem to get completely swallowed up in the void.

Over the centuries, many have thought it absurd to think that we are the only ones. For example, Anaxagoras, Epicurus, Lucretius, and, later, Giordano Bruno, Huygens and Kepler were all confident that the universe is teeming with life. Kant was willing to bet everything he had on the existence of intelligent life on other planets. And we now know that there is a vast multitude of Earth-like planets even in our own little galaxy.

The experience of cosmic insignificance is often blamed on the rise of modern science, and the decline of religious belief. Many think that things started to take a turn for the worse with Copernicus. Nietzsche, for example, laments ‘the nihilistic consequences of contemporary science’, and adds that

Since Copernicus it seems that man has found himself on a descending slope—he always rolls further and further away from his point of departure toward… —where is that? Towards nothingness?

Freud later wrote about a series of harsh blows to our self-esteem delivered by science. The first blow was delivered by Copernicus, when we learned, as Freud puts it, that “our earth was not the centre of the universe but only a tiny fragment of a cosmic system of scarcely imaginable vastness…”

It is still common to refer, in a disappointed tone, to the discovery that we aren’t at the centre of God’s creation, as we had long thought, but located, as Carl Sagan puts it, “in some forgotten corner”. We live, Sagan writes, “on a mote of dust circling a humdrum star in the remotest corner of an obscure galaxy.”

by Nick Hughs and Guy Kuhane

by Nick Hughs and Guy Kuhane hour – it would take us 100,000 years to cross the Milky Way. But we still wouldn’t have gone very far. Our modest Milky Way galaxy contains 100–400 billion stars. This isn’t very much: according to the latest calculations, the observable universe contains around 300 sextillion stars. By recent estimates, our Milky Way galaxy is just one of 2 trillion galaxies in the observable Universe, and the region of space that they occupy spans at least 90 billion light-years. If you imagine Earth shrunk down to the size of a single grain of sand, and you imagine the size of that grain of sand relative to the entirety of the Sahara Desert, you are still nowhere near to comprehending how infinitesimally small a position we occupy in space. The American astronomer Carl Sagan put the point vividly in 1994 when discussing the famous ‘Pale Blue Dot’ photograph taken by Voyager 1. Our planet, he said, is nothing more than ‘a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam’. Stephen Hawking delivers the news more bluntly. We are, he says, “just a chemical scum on a moderate-sized planet, orbiting round a very average star in the outer suburb of one among a hundred billion galaxies.”

hour – it would take us 100,000 years to cross the Milky Way. But we still wouldn’t have gone very far. Our modest Milky Way galaxy contains 100–400 billion stars. This isn’t very much: according to the latest calculations, the observable universe contains around 300 sextillion stars. By recent estimates, our Milky Way galaxy is just one of 2 trillion galaxies in the observable Universe, and the region of space that they occupy spans at least 90 billion light-years. If you imagine Earth shrunk down to the size of a single grain of sand, and you imagine the size of that grain of sand relative to the entirety of the Sahara Desert, you are still nowhere near to comprehending how infinitesimally small a position we occupy in space. The American astronomer Carl Sagan put the point vividly in 1994 when discussing the famous ‘Pale Blue Dot’ photograph taken by Voyager 1. Our planet, he said, is nothing more than ‘a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam’. Stephen Hawking delivers the news more bluntly. We are, he says, “just a chemical scum on a moderate-sized planet, orbiting round a very average star in the outer suburb of one among a hundred billion galaxies.”