Secret History of The Early Church

by F. Tupper Saussy

by F. Tupper Saussy

IN PAGAN ROME the public servants were priests of the various gods and goddesses. Monetary affairs, for example, were governed by priests of the goddess Moneta. Priests of Dionysus managed architecture and cemeteries, while priests of Justitia, with her sword, and Libera, blindfolded, holding her scales aloft, ruled the courts. Hundreds of priestly orders, known as the Sacred College, managed hundreds of government bureaus, from the justice system to the construction, cleaning, and repair of bridges (no bridge could be built without the approval of Pontifex Maximus), buildings, temples, castles, baths, sewers, ports, highways, walls and ramparts of cities and the boundaries of lands.

Priests directed the paving and repairing of streets and roads, supervised the calendar and the education of youth. Priests regulated weights, measures, and the value of money. Priests solemnized and certified births, baptisms, puberty, purification, confession, adolescence, marriage, divorce, death, burial, excommunication, canonization, deification, adoption into families, adoption into tribes and orders of nobility. Priests ran the libraries, the museums, the consecrated lands and treasures. Priests registered the trademarks and symbols. Priests were in charge of public worship, directing the festivals, plays, entertainments, games and ceremonies. Priests wrote and held custody over wills, testaments, and legal conveyances.

By the fourth century, one half of the lands and one fourth of the population of the Roman Empire were owned by the priests. When the Emperor Constantine and his Senate formally adopted Christianity as the Empire’s official religion, the exercise was more of a merger or acquisition than a revolution. The wealth of the priests merely became the immediate possession of the Christian churches, and the priests merely declared themselves Christians. Government continued without interruption. The pagan gods and goddesses were artfully outfitted with names appropriate to Christianity. The sign over the Pantheon indicating “To [the fertility goddess] Cybele and All the Gods” was re-written “To Mary and All the Saints.” The Temple of Apollo became the Church of St. Apollinaris. The Temple of Mars was reconsecrated Church of Santa Martina, with the inscription “Mars hence ejected, Martina, martyred maid/claims now the worship which to him was paid.”

Haloed icons of Apollo were identified as Jesus, and the crosses of Bacchus and Tammuz were accepted as the official symbol of the Crucifixion. Pope Leo I decreed that “St. Peter and St. Paul have replaced Romulus and Remus as Rome’s protecting patrons.” Pagan feasts, too, were Christianized. December 25 – the celebrated birthday of a number of gods, among them Saturn, Jupiter, Tammuz, Bacchus, Osiris, and Mithras – was claimed to have been that of Jesus as well, and the traditional Saturnalia, season of drunken merriment and gift-giving, evolved into Christmas.

Bacchus was popular in ancient France under his Greek name Dionysus – or, as the French rendered it, Denis. His feast, the Festun Dionysi, was held every seventh day of October, at the end of the vintage season. After two days of wild partying, another feast was held, the Festun Dionysi Eleutherei Rusticum (“Country Festival of Merry Dionysus”). The papacy cleverly brought the worshipers of Dionysus into its jurisdiction by transforming the words Dionysus, Bacchus, Eleutherei, and Rusticum into . . . a group of Christian martyrs. October seventh was entered on the Liturgical Calendar as the feast day of “St. Bacchus the Martyr,” while October ninth was instituted as the “Festival of St. Denis, and of his companions St. Eleuthere and St. Rustic.” The Catholic Almanac (1992 et seq) sustains the fabrication by designating October ninth as the:

“Feast Day of Denis, bishop of Paris, and two companions identified by early writers as Rusticus, a priest, and Eleutherius, a deacon martyred near Paris. Denis is popularly regarded as the apostle and patron saint of France.”

Playing loose with truth and Scripture in order to bring every human creature into subjection to the Roman Pontiff is a technique called “missionary adaptation.” This is explained as “the adjustment of the mission subject to the cultural requirements of the mission object” so that the papacy’s needs will be brought “as much as possible in accord with existing socially shared patterns of thought, evaluation, and action, so as to avoid unnecessary and serious disorganization.”

Rome has so seamlessly adapted its mission to American secularism that we do not think of the United States as a Catholic system. Yet the rosters of government rather decisively show this to be the case.

By far the greatest challenge to missionary adaptation has been Scripture – that is, the Old and New Testaments, commonly known as the Holy Bible. Almost for as long as Rome has been the seat of Pontifex Maximus, there has been a curious enmity between between the popes and the Bible whose believers they are presumed to head.

Part II

Part II

EVERY RULED SOCIETY has some form of holy scripture. The holy scriptures of Caesarean Rome were the prophecies and ritual directions contained in the ten Sibylline gospels and Virgil’s Aeneid.

The Aeneid implied that every Roman’s duty was to sacrifice his individuality, as heroic Aeneas had done, to the greater glory of Rome and Pontifex Maximus. The Sibyllines, borrowing from Isaiah’s much earlier prophecy of Jesus Christ, prophesied that when Caesar Augustus succeeded his uncle Julius as Pontifex Maximus he would rule the world as “Prince of Peace, Son of God.” Augustus would issue in a “new world order,” as indeed he did.

The Sibyllines and the Aeneid were so beloved by the government priests that they were considered part of the Roman constitution. The same scriptures were made part of the United States Constitution when the mottoes “ANNUIT COEPTIS” and “NOVUS ORDO SECLORUM,” taken from the Aeneid and the Sibyllines respectively, were incorporated, by the Act of July 28, 1782, into the Great Seal of the United States.

The Sibyllines and the Aeneid were open only to priests and certain privileged persons. The people learned their sacred content by the trickle-down of priestly retelling. When the Old and New Testaments were adopted as the Empire’s official sacred writings they, too, were given to the exclusive care of the priests. And in accord with Roman tradition, the people learned sacred content from discretionary retelling. This had to be, for the sake of the Holy Empire. For should the people acquire biblical knowledge, they would know that Pontifex Maximus was not a legitimate Christian entitlement. Knowing this, they would not bow to his supremacy. The Empire could collapse. And so the monarchial Roman Church forcibly suppressed the Bible’s intelligent reading. This is why the millennium between Constantine and Gutenberg is known as “the Dark Ages.”

Sprinkled throughout the Empire, however, were isolated Christian assemblies who had preserved Scripture from the days of the early Church. For them the Bible invited an ongoing, personal communion with the Creator of the universe. They lived by the writings of which Rome was so jealous. By the thirteenth century, these assemblies had grown so vibrant that Pope Gregory IX declared unauthorized Bible study a heresy. He further decreed that “it is the duty of every Catholic to persecute heretics.” To manage the persecution, Gregory established the Pontifical Inquisition.

The Inquisition treated the slightest departure from the life of the community as proof of direct communion with the Bible or Satan. Either instance was a sin worthy of death. Cases were prosecuted according to a strict routine. First, the inquisitors would enter a town and present their credentials to the civil authorities. In the pope’s name, they would require the governor’s cooperation. Next, the local priest would be ordered to summon his congregation to hear the inquisitors preach against heresy, which was defined as anything the least bit opposed to the papal system. A brief grace period followed the sermon, wherein the people were given an opportunity to step forward and accuse themselves of crimes. Those who did were usually punished mildly. Later, the inquisitors would receive at their lodgings unverified accusations, guaranteeing in the pope’s name the anonymity of informants. Many innocent lives were ruined by false testimony.

Trials were conducted arbitrarily and secretly by tribunals consisting of the inquisitors, their staffs, and their witnesses, all concealed under hoods. The accused were never told the charges against them, and they were forbidden to ask. No defense witnesses were permitted. The accused had but one option: to confess guilt and die. Those who refused to confess (and witnesses who balked at testifying) were carried to the dungeon for torture sessions (boys under fourteen and girls under twelve exempted). Inquisitors and executioners were commanded by papal edict to show no mercy. No acquittal was ever recorded. Every fully prosecuted case ended in the death of the defendant and the forfeiture of his or her property, since it was assumed (as in American forfeiture cases since 1984) that the property was gained in sin. Sometimes the property of family members for generations to come was forfeited. These forfeitures were paid out in expenses to the scribes and executioners, half of the remainder going into the papal treasury and half to the inquisitors. Although popes and inquisitors amassed great fortunes from the Inquisition, its greatest beneficiary was, and has been, the Roman system.

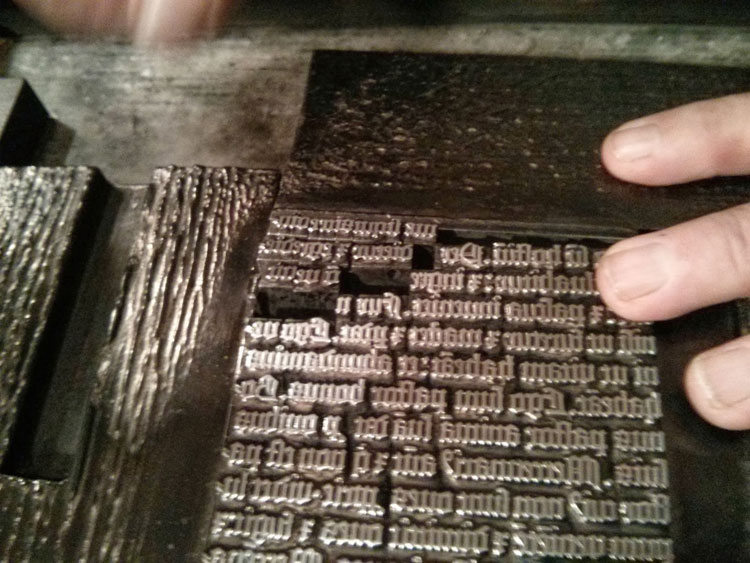

The Inquisition was most effective against the isolated truthseeker in an ignorant community. As communities became more literate, the Inquisition grew subtler. What brought literacy to communities was the epidemic of Bible-reading made possible by the perfection of Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of movable type.

Part III

Part III

GUTENBERG CHOSE the Bible to demonstrate movable type not so much that the common man might be brought nearer to God, but that he and his backer, Dr. Johannes Faust, might make a killing in the book trade.

Prior to 1450, Bibles were so rare they were conveyed by deed, like parcels of real estate. A Bible took nearly a year to make, commanding a price equal to ten times the annual income of a prosperous man. Johannes Gutenberg intended his first production, a folio edition of the 6th-century Latin Bible (known as the Vulgate), to fetch manuscript prices. Dr. Faust discreetly sold it as a one-of-a-kind to kings, nobles, and churches. A second edition in 1462 sold for as much as 600 crowns each in Paris, but sales were too sluggish to suit Faust, so he slashed prices to 60 crowns and then to 30.

This put enough copies into circulation for Church authorities to notice that several were identical. Such extraordinary uniformity being regarded as humanly impossible, the authorities charged that Faust had produced the Bibles by magic. On this pretext, the Archbishop of Mainz had Gutenberg’s shop raided and a fortune in counterfeit Bibles seized. The red ink with which they were embellished was alleged to be human blood. Faust was arrested for conspiring with Satan, but there is no record of any trial.

Meanwhile, the pressmen, who had been sworn not to disclose Gutenberg’s secrets while in his service, fled the jurisdiction of Mainz and set up shops of their own. As paper manufacture improved, along with technical improvements in matrix cutting and type-casting, books began to proliferate. Most were editions of the Vulgate. In the decade following the Mainz raid, five Latin and two German Bibles were published. Translators busied themselves in other countries. An Italian version appeared in 1471 , a Bohemian in 1475 , a Dutch and a French in 1477 , and a Spanish in 1478. As quickly as our generation has become computer-literate, the Gutenberg generation learned to read books, and careful readers found shocking discrepancies between the papacy’s interpretation of God’s Word and the Word itself.

In 1485, the Archbishop of Mainz issued an edict punishing unauthorized Bible-reading with excommunication, confiscation of books, and heavy fines. The great Renaissance theologian Desiderius Erasmus challenged the Archbishop by publishing, in 1516, the first printed edition of the Greek New Testament. He addressed the anti-Bible mentality in his preface with these words:

“I vehemently dissent from those who would not have private persons read the Holy Scriptures nor have them translated into the vulgar tongues, as though either Christ taught such difficult doctrines that they can only be understood by a few theologians, or the safety of the Christian religion lay in ignorance of it. I should like all women to read the Gospel and the Epistles of Paul. Would that they were translated into all languages so that not only the Scotch and Irish, but Turks and Saracens might be able to read and know them.”

A Catholic monk named Martin Luther, against the advice of his superiors, plunged into the New Testament of Erasmus. He was shocked by the absence of scriptural authority for so many Church traditions. Of the seven Church Sacraments only two, Baptism and the Lord’s Supper, were grounded in Scripture. The remaining five – Confirmation, Absolution, Ordination, Marriage, and Extreme Unction – were the inventions of post-biblical councils and decrees. Luther found no scriptural mandate for celibacy of monks and nuns, or for pilgrimages and the veneration of sacred relics. The Church taught that prayer, good works, and regular participation in the Sacraments might save man from eternal damnation. Luther found this to be opposed to the teaching of Scripture. According to Scripture, only one thing can save man from the consequences of his sins: God’s grace, and that alone.

The most explosive result of Luther’s Bible-reading was its attitude toward the papacy. Nowhere in Scripture could the passionate monk find that God had ordained an imperious Roman “Vicar of Christ” to rule over a vast economy based on selling rights to do evil. These rights were called indulgences. They had been a Church tradition since Pope Leo III had begun granting them in the year 800, payable in the money coined by Pope Adrian I in780.

Indulgences were floated on the Church’s credibility, rather like government bonds are issued on the credibility of states today. In 1491, for example, Innocent VII granted the 20-year Butterbriefe indulgence, by which Germans could pay 1/20th of a guilder for the annual privilege of eating dairy products even while meriting from fasting. The proceeds of the Butterbriefe went to build a bridge at Torgau. Rome’s indulgence economy was as extensive as America’s income tax system today. And it was every bit as fueled by the people’s trembling compliance, voluntarily, to a presumption of liability.

In 1515 Pope Leo X issued a Bull of Indulgence authorizing letters of safe conduct to Paradise and pardons for every evil imaginable, from a 25-cent purgatory release (the dead left purgatory the instant one’s coins hit the bottom of the indulgence-salesman’s bucket) to a license so potent that it would excuse someone who had raped the Virgin Mary. For the payment of four ducats, one could be forgiven for murdering one’s father. Sorcery was pardoned for 6 ducats. For robbing a church, the law could be relaxed for only 9 ducats. Sodomy was pardoned for 12 ducats. Half the revenues from Leo’s indulgence went to a fund for the building of St. Peter’s Cathedral, and the other half to paying 40% interest rates on bank loans subsidizing the magnificent works of art and architecture with which His Holiness was establishing Rome as the cultural capital of the Renaissance. Historians have glorified Leo, whose father happened to be the great Florentine banker Lorenzo d’Medici, by marking the sixteenth century as “the Century of Leo X.”

In early 1521 , Martin Luther formally protested the indulgence racket by nailing his famous Ninety-five Theses Upon Indulgences to the door of the castle church of Wittenburg. The church was said to own a lock of the Holy Virgin’s hair worth two million years of indulgences. Luther’s Theses exhorted Christians “to follow Christ, their Head, through penalties, deaths, and hells,” rather than purchase “a false assurance of peace” from Church indulgence-salesmen.

Leo had Luther arrested and detained for ten months in Wartburg Castle. While in custody, Luther managed to translate the Greek New Testament of Erasmus into German. Its publication alarmed the broadest reaches of Roman authority. D’Aubigne, in his History of the Reformation, tells us that “Ignorant priests shuddered at the thought that every citizen, nay every peasant, would now be able to dispute with them on the precepts of our Lord.”

Meanwhile, Leo X died. The new pope, Adrian VI, hardly eulogized Leo when confessing to the Diet of Nuremberg that “for many years, abominable things have taken place in the Chair of Peter, abuses in spiritual matters, transgressions of the Commandments, so that everything here has been wickedly perverted.” Adrian died shortly after speaking these lines, to be succeeded by the Cardinal who had been handling Martin Luther’s case all along, another Medici, Leo X’s first cousin, Giulio d’Medici. Giulio took the papal name Clement VII.

Just as Leo X’s corruption had ignited Luther, Clement VII’s shrewdness determined how the Church would deal with the proliferation of Bibles. Clement was personally advised by Niccolo Machiavelli, inventor of modern political science, and Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, Chancellor of England that both printing and Protestantism could be turned to Rome’s advantage by employing movable type to produce a literature that would counteract this trend but instead, unbeknownst to them, it would only speed further the Reformation. Cardinal Wolsey, who later found the Christ Church College at Oxford, characterized this project as “to put learning against learning.”

Against the Bible’s learning, which demonstrated how man could have eternal life simply by believing in the facts of Christ’s death and resurrection, would be put the teachings of the gnostics. Gnosticism inferred that man could achieve everlasting life by doing good works himself.

An enormous trove of gnostic teachings had been brought from the eastern Mediterranean by agents of Clement VII’s great-grandfather, Cosimo d’Medici. Suppressed since the Emperor Justinian had shut down these so-called pagan colleges of Athens back in 529, these celebrated mystical, scientific and philosophical scrolls and manuscripts empowered humanity. They taught that human intelligence was competent to determine truth from falsehood without guidance or assistance from any god. Since, as Protagoras put it, “man is the measure of all things,” man could control the living powers of the universe.

Cosimo had stored huge quantities of this material in his library in Florence. The Medici Library, whose final architect was Michaelangelo, welcomed scholars favored by Clement VII. These scholars soon began focusing more upon humanity’s awakening rather than upon biblical theosophy. So extensive was the Medici Library’s philosophical influence that even scholars today consider it the cradle of Western civilization.

Posted in True History of Manwith comments disabled.