Steps To The Stars

by Timothy Good

by Timothy Good

It was the evening of 4 July 1949. For Daniel Fry, a rocket test technician employed by Aerojet General Corporation at the vast and remote White Sands  Proving Grounds in New Mexico, it was to be an Independence Day with a difference.

Proving Grounds in New Mexico, it was to be an Independence Day with a difference.

Fry had planned on going into the town of Las Cruces to celebrate with colleagues, but having missed the last motor pool bus, he went back to his room and began reading a textbook on heat transfer, a problem of considerable relevance to the design of rocket motors. ‘I was soon to learn however,’ said Fry, ‘that the problems of heat transfer can become as uncomfortable physically as they are interesting academically.’ At 20.00 the building’s air conditioning system apparently broke down and it became unbearably hot. He decided to go for a walk, hoping it would be cooler outside.

Heading in the direction of an old static test stand, where Aerojet at the time were mounting their largest rocket engine for tests, Fry then decided to take a different route that led off towards the base of the Organ Mountains. Scanning the evening sky, he was surprised to notice one star, then another, then two more, ‘going out’. Suddenly, the outline of an object of some sort, blending with the dark blue of the sky, appeared to be headed in his direction. ‘As it continued to come toward me, I felt a strong inclination to run,’ he explained, ‘but experience in rocketry had taught me that it is foolish to run from an approaching missile until you are sure of its trajectory, since there is no way to judge the trajectory of an approaching object if you are running.’

The object was now less than a few hundred feet away, moving more slowly and seeming to decelerate. Its shape was an oblate spheroid with a diameter at its largest part of about 30 feet. ‘Somewhat reassured by its rapid deceleration,’ continued Fry, ‘I remained where I was and watched it glide, as lightly as a bit of thistledown floating in the breeze. About 70 feet away from where I was standing, it settled to the ground without the slightest bump or jar. Except for the crackling of the brush upon which it had settled, there had been no sound at all. For what seemed a long time . . . I stared at the now motionless object as a child might stare at the rabbit which a stage magician has just pulled from his hat. I knew it was impossible, but there it was!’

Fry had been employed for many years in the burgeoning field of astronautics, yet never before had he seen such a device. As Vice-President of Crescent Engineering and Research Company in California, for example, he developed a number of parts for the guidance system of the Atlas missile, while at Aerojet he was in charge of installation of instruments for missile control and guidance systems. ‘Obviously, the intelligence and the technology that had designed and built this vehicle had found the answers to a number of questions which even our most advanced physicists have not yet learned to ask,’ Fry commented. He then cautiously approached to within a few feet of the landed craft and listened for any sign of life or sound from within. There was none.

I began to circle slowly about the craft so that I could examine it more completely. It was . . . a spheroid, considerably flattened at the top and bottom. The vertical dimension was about 16 feet, and the horizontal dimension about 30 feet at the widest point, which was about seven feet from the ground. Its curvature was such that, if viewed from directly below, it might appear to be saucer-shaped, but actually it was more nearly like a soup bowl inverted over a sauce dish.

The dark blue tint which it had seemed to have when in the air was gone now, and the surface appeared to be of highly polished metal, silvery in color, but with a slight violet sheen. I walked completely around the thing without seeing any sign of doors, windows or even seams . . . I stepped forward and cautiously extended my index finger until it touched the metal surface. It was only a few degrees above the air temperature, but it had a quality of smoothness that seized my attention at once. It was simply impossible to produce any friction between my fingertip and the metal. No matter how firmly I pressed my finger on the metal, it drifted around on the surface as though there were a million tiny ball-bearings between my finger and the metal. I then began to stroke the metal with the palm of my hand, and could feel a slight but definite tingling in the tips of my fingers and the heel of my palm.

The Voice

Suddenly, a loud male voice came out of nowhere: ‘Better not touch the hull, pal, it’s still hot!’ Shocked, Fry leaped backwards several feet, catching his heel in a low bush and sprawling full length in the sand. Something like a low chuckle was heard, then the voice came back: ‘Take it easy, pal, you’re among friends.’ Recovering himself, Fry looked around for some person or gadget from which the voice came, but could see none. He complained to the voice that it should turn the volume down. ‘Sorry, buddy, but you were in the process of killing yourself and there wasn’t time to diddle with controls,’ came the response. ‘Do you mean the hull is highly radioactive?’ asked Fry. ‘If so, I am much too close.’

‘It isn’t radioactive in the sense that you use the word,’ replied the voice. ‘I used the term “hot” because it was the only one I could think of in your language to explain the condition. The hull has a field about it which repels all other matter. Your physicists would describe the force involved as the “anti” particle of the binding energy of the atom.’ The ‘voice’ expounded at length as Fry recalled in detail:

When certain elements such as platinum are properly prepared and treated with a saturation exposure to a beam of very high energy photons, the anti-binding energy particle will be generated outside the nucleus. Since these particles tend to repel each other, as well as all other matter, they, like the electron, tend to migrate to the surface of the metal where they manifest as a repellent force. The particles have a fairly long half-life, so that the normal cosmic radiation received by the craft when in space is sufficient to maintain an effective charge. The field is very powerful at molecular distances but, like the binding energy, it follows the seventh power law so that the force becomes negligible a few microns away from the surface of the hull.

Perhaps you noticed that the hull seemed unusually smooth and slippery. That is because your flesh did not actually come into contact with the metal but was held a short distance from it by the repulsion of the field. We use the field to protect the hull from being scratched or damaged during landings. It also lowers air friction greatly when it becomes necessary to travel at high speed through any atmosphere. The field produces an almost perfect laminar flow of air or any gas about the craft, and little heat is generated or transmitted to the hull.

‘But how would this kill me?’ asked Fry. ‘I did touch the hull and felt only a slight tingle in my hand. And what did you mean by that remark about my language? You sound pretty much American to me.’

Replying to the first question, the voice explained that Fry would have probably died within a few months from exposure to the ‘force field’, which produces ‘what you would describe as “antibodies” in the blood stream that are absorbed by the liver, causing the latter to become greatly enlarged and congested. ‘In your case,’ continued the voice, ‘the exposure was so short and over such a small area that you are not in any great danger, although you will probably feel some effects sooner or later, provided, of course, that your biological functions are similar to ours, and we have good reason to believe they are.’ The voice continued:

As to your second question, I am not an American such as you, nor even an ‘Earthian’, although my present assignment requires me to become both. The fact that you believed me to be one of your countrymen is a testimonial to the effort I have expended to learn and to practice your language. If you talked with me for any length of time, however, you would begin to notice that my vocabulary is far from complete, and many of my words would seem outdated and perhaps obsolete. As a matter of fact, I have never yet set foot upon your planet. It will require at least four more of your years for me to become adapted to your environment, including your stronger gravity, [and] your atmosphere . . . I will also require the complete cooperation of someone like yourself who is already a resident of the planet.

Fry stood silently for what seemed a long time, attempting to come to terms with the profound implications of what he had seen and heard. The conversation then continued, with Fry asking a variety of questions, the first dealing with his reactions to the experience. The voice was encouraging:

One of the purposes of this visit is to determine the basic adaptability of the Earth’s peoples, particularly your ability to adjust your minds quickly to conditions and concepts completely foreign to your customary modes of thought. Previous expeditions by our ancestors, over a period of many centuries, met with almost total failure in this respect. This time there is hope that we may find minds somewhat more receptive so that we may assist you in the progress, or at least in the continued existence of your race . . . The fact that, in spite of being in circumstances completely unique in your experience, you are listening calmly to my voice and making logical replies is the best evidence that your mind is of the type we hoped to find.

Fry thanked the voice, but pointed out that this statement implied that he was to be used in some project involving the advancement of the people of Earth. ‘Why me?’ he asked. ‘Is it just because I accidentally happened to be here when you landed? I could easily put you in touch with a number of men right here at the test base who could be of far more value to you than I.’

‘Perhaps they could,’ came the reply, ‘but would they?’

If you think you are here by accident, you greatly underestimate our abilities. Why do you think the dispatcher at your motor pool gave you incorrect information? Why did you think your air-conditioning system had failed tonight when, as a matter of fact, it was functioning perfectly? Why do you think you turned off on this small road, when your intention had been to go to your static test stand? And finally, why do you think you changed your mind about going back to your base to report [as had been Fry’s initial intention] the arrival of our sampling carrier? It is seldom that we superimpose our will upon that of others . . . but this is a case of such urgency for your people that we felt an exception to the rule was warranted . . .

The voice went on to request Fry’s assistance in a planned programme for ‘the welfare, and in fact for the preservation of’ Earth’s people. Several years would pass, Fry was told, before his services would be required. ‘We will be glad to offer you a short test flight in the sampling craft if it will help you to decide that we are what we say, and that our technology has much for you to learn,’ said the voice, and continued:

The craft is a remotely controlled sampling device, or cargo carrier, and while I am speaking through its communication system, I am not in it. I am in a much larger deep space transport ship, or what you would call a ‘Mother Ship’. At present, it is some 900 of your miles above the surface of your planet, which is as close as ships of this size are permitted to approach any planet with an appreciable atmosphere. The cargo craft is being used to bring us samples of your atmosphere so that my lungs may gradually become accustomed to it . . .

All of the previous atmosphere that was in the craft was allowed to escape while it was in space, by the opening of the remotely controlled valve in the top. There is now an almost perfect vacuum inside. When the port is again opened, which I shall do now, your air will rush in to fill the craft, and we will have a large-scale sample of your atmosphere, together with any micro-organisms which may be present in it. We need these also, for study and for immunization. Your breathing of the atmosphere during this short demonstration flight will, of course, distort this particular sample somewhat, but we will have ample opportunity to obtain others before my adaptation to the environment of your planet is complete.

Inside The Craft

A sound – partly a hiss and partly a murmur – came from the top of the craft. This lasted for about 15 seconds, then all became quiet again. ‘Any port large enough to have filled a ship of that size with air in 15 seconds should have produced quite a roar,’ Fry reasoned. ‘I realized then that the walls of the ship were almost, if not entirely, soundproof, and since most of the sound of the entering air would be produced inside, very little would be audible outside.’

A single click was then heard coming from the lower wall of the craft, and a section of the lower side of the hull moved back on itself for a few inches then moved sideways, disappearing into the wall of the hull and leaving an oval-shaped opening about five feet in height and some three feet in width at its widest point. Fry walked towards the hatch and, ducking slightly, went inside the craft. With his feet still on the ground, owing to the curvature of the craft, he looked around.

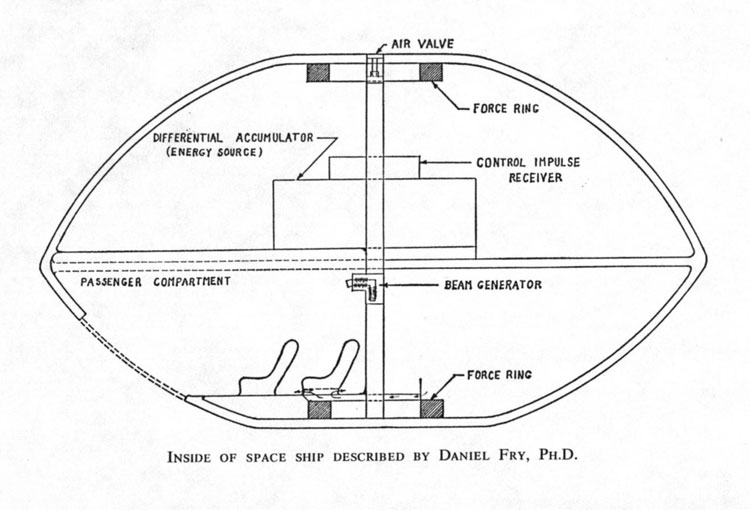

The compartment into which I was looking occupied only a small portion of the interior of the ship. It was a room about nine feet deep and seven feet wide, with a floor about 16 inches above the ground and a ceiling between six and seven feet above the floor. The walls were slightly curved and the intersections of the walls were beveled so that there were no sharp angles or corners . . .

The room contained four seats; they looked much like our modern body contour chairs, except that they were somewhat smaller . . . The seats faced the opening in which I was standing, and were arranged in two rows of two each in the center of the room, leaving an aisle between the seats and either wall. In the center of the rear wall, where it joined the ceiling, there was a small box or cabinet with a tube and what appeared to be a lens arrangement. It was somewhat similar to a small motion picture camera or projector, except that no film spools or other moving parts were visible. Light was coming from the lens. It was not a beam of light such as would have come from a projector, but a diffused glow . . . it still furnished ample light for comfortable seeing in the small compartment.

Fry noted that the seats and the light seemed to be the only furnishings in an otherwise bare metal room. ‘Not a very inviting cabin,’ he thought, ‘looks more like a cell.’

Fry noted that the seats and the light seemed to be the only furnishings in an otherwise bare metal room. ‘Not a very inviting cabin,’ he thought, ‘looks more like a cell.’

‘It’s only a sampling carrier,’ said the voice, in response to Fry’s unspoken thought, ‘and was not really designed or intended to carry passengers: the small compartment was designed for emergencies only, but you will find the seats quite comfortable. Step in and take a seat if you wish to make this test flight.’

Fry stepped up on to the floor and headed towards the nearest seat. As he did so, he heard a click as the door began to slide out of the recess in the wall behind him. ‘Instinctively, I turned as though to leap out to the comparative safety of the open desert behind me, but the door was already closed. If this was a trap, I was in it now, and there was no point in struggling against the inevitable.’

‘Where would you like to go?’ asked the voice, now seeming to come from all around Fry, rather than beside him, as before. ‘I don’t know how far you can take me in whatever time you have,’ he replied. ‘And since this compartment has no windows, it won’t matter which way we go, as I won’t be able to see anything.’

‘You will be able to see,’ came the reply, ‘at least, as much as you could see from any of your vehicles in the air at night. If you would like a suggestion, we can take you over the city of New York and return you here in about 30 minutes. At an elevation of about 20 of your miles, the light patterns of your major cities take on an especially fascinating appearance which we have never seen in connection with any other planet.’

‘To New York – and back – in 30 minutes?’ retorted Fry. ‘Your minutes must be very different from ours. New York is 2,000 miles from here. A round trip would be 4,000 miles. To do it in half an hour would require a speed of 8,000 miles per hour! How can you produce and apply energies of that order in a craft like this, and how can I take the acceleration? You don’t even have belts on these seats!’

‘You won’t feel the acceleration at all,’ came the reassuring reply. ‘Just take a seat and I will start the craft. . .’

Fry took the seat nearest to the door and found it to be quite comfortable. ‘The material of which it was made felt like foam rubber with a vinylite covering. However, there were no seams or joints such as an outer covering would require, so the material, whatever it was, probably had been molded directly into its frame in a single operation.’

On Rendering Materials Translucent

‘I will now turn off the compartment light and activate the viewing beam,’ said the voice. For a moment the room became completely dark. Then a beam of light came from the projector. ‘The beam, or the part of it which was visible at all, was a deep violet, at the very top of the visible spectrum,’ Fry explained. ‘The beam was focused so as to exactly cover the door through which I had come, and under its influence the door became totally transparent. It was as though I were looking through the finest type of plate glass or Lucite window.’

As the voice went on to say that a few of the basic technical principles would be explained, Fry began to realize that the words he had been hearing were probably not coming to his ears as sound waves but seemed to be originating directly in his brain. The voice continued:

As you see, the door has become transparent. This startles you because you are accustomed to thinking of metals as being completely opaque. However, ordinary glass is just as dense as many metals and harder than most, and yet transmits light quite readily. Most matter is opaque to light because the photons of light are captured and absorbed in the electron orbits of the atoms through which they pass. This capture will occur whenever the frequency of the photon matches one of the frequencies of the atom. The energy thus stored is soon re-emitted, but usually in the infra-red portion of the spectrum, which is below the range of visibility, and so cannot be seen as light. There are several ways in which matter can be made transparent, or at least translucent.

One method is to create a field matrix between the atoms which will tend to prevent the photon from being absorbed. Such a matrix develops in many substances during crystallization. Another is to raise the frequency of the photon above the highest absorption frequency of the atoms. The beam of energy which is now acting upon the metal of the door is what you would call a ‘frequency multiplier’. The beam penetrates the metal and acts upon any light that reaches it in such a way that the resulting frequency is raised to that between the ranges which you describe as the ‘X-ray’ and the ‘Cosmic Ray’ spectrums. At these frequencies, the waves pass through the metal quite readily. Then, when these leave the metal on the inner side of the door, they again interact with the viewing beam, producing what you would describe as ‘beat frequencies’ which are identical with the original frequencies of the light. As a rough analogy, the system could be compared to the carrier wave of one of your radio broadcasting stations, except that the modulation is applied ‘upstream’ as it were, instead of at the source of the carrier.

Earth’s Broadcasts Monitored

Fry remarked that, for one who had never set foot on Earth, his unseen host seemed extraordinarily familiar with our terrestrial technology. ‘You are underestimating our technology,’ came the reply.

You have no idea of the amount of close-range observation to which your planet has been subjected by passing space craft during the past few generations. The radio messages and programs which you continually hurl into space can readily be monitored by our receiving equipment, at distances equal to several times the diameter of your solar system. Within such a volume of space there will always be at least a few ships either passing through the system or pausing to store up energy from its solar radiation. Any data received from earthly broadcasts which is considered to be of potential interest to other races will be recorded and relayed to more distant receiving points which will relay in turn, until the data is ultimately available to much of the galaxy.

Lift-Off

The voice announced the imminent departure of the craft. ‘A moment later, the ground suddenly fell away from the ship with almost incredible rapidity,’ said Fry. ‘I did not feel the slightest sense of motion myself, and the ship seemed to be as steady as a rock . . . the lights of the army base at the proving ground, which had been hidden by a low hill, instantly came into sight. . . A few seconds later the lights of the town of Las Cruces came into view . . . and I knew that we must have risen at least 1,000 feet in those few seconds. The ship was rotating slightly to my left as it rose, and I was able to see the highway from Las Cruces to El Paso [Texas] . . . I could even distinguish the very thin dark line of the Rio Grande . . . The surface of the Earth appeared to be glowing with a slightly greenish phosphorescence. The sky outside the ship had become much darker, and the stars seemed to have doubled in brilliance.’ He assumed that the craft had now entered the stratosphere, in which case an altitude of more than 10 miles must have been attained in no more than 20 seconds, and without the slightest sense of acceleration.

‘You are now about 13 miles above the surface,’ announced the voice, ‘and you are rising at about one half-mile per second. We have brought you up rather slowly so that you might have a better opportunity to view your cities from the air. We will take you up 35 miles for the horizontal flight. . .’

Gravitational Fields

The voice explained the question of acceleration and why it had no effect on the occupants of their craft; a question ‘which seems to have come up quite often in the minds of the men of science, and many others of your people’.

Whenever our sampling devices or landing vehicles have been observed by them, and when the velocities and acceleration are described, disbelief is always apparent. . . This has been one of the causes of disappointment to us in our evaluation of the intelligence of the people of Earth . . . The answer is simply that the force which we use to accelerate our vehicles is identical in nature to a gravitational field. It acts, not only upon every atom of the vehicle, but equally upon every atom of mass that is within it, including the mass of the pilot and any passengers. Regardless of the intensity of the field therefore, every particle of mass within the influence of the field is in a uniform state of acceleration or, as you would term it, free fall, with respect to the field. Under these circumstances acceleration has no effect upon the vehicle or anything within it.

‘But in that case,’ asked Fry, ‘why am I not floating around in the air as things are supposed to do in a missile that is in free fall?’ Back came the answer:

Before the ship’s own field was generated, it was resting upon the earth, and you were resting upon the seat. There was a force of one gravity acting between your body and your seat. Since the force which accelerates both the ship and your body acts in exact proportion to the mass, and since the Earth’s gravity continues to act upon both, the original force between your body and the seat will remain constant except that it will decrease as the force of gravity of the planet decreases with distance. When traveling between planetary or stellar bodies far from any natural gravity source, we find it necessary, for practical reasons, to reproduce this force artificially.

The gravity to which we are accustomed is but little more than one-half that of Earth. It is one of the reasons that it will require so much time for one of us to become completely acclimatized to your environment. If I were to land now upon your planet, I could tolerate the doubled gravitational force for a time but the double weight of all my internal organs would cause them to be displaced downward, seriously hampering their functions. The difference in blood pressure between head and feet when standing erect would be double that to which we are accustomed, and there would be several other complications . . . If, on the other hand, I remain in my own ship, the gravitational force to which I am subject can be increased by small but regular increments: the supporting tissues will gradually increase in size and strength until, eventually, your gravity will become as normal to me as my own is now.

Fry asked for an explanation of the craft’s propulsion system, specifically as it related to the tremendous amount of energy presumably required to accelerate the ship to such fantastic velocities. The voice began by saying that there were several concepts and words which did not yet exist in human vocabulary, or even in human consciousness, to allow for a complete explanation. But after several analogies by way of simplification, he continued:

The large drum-like structure just above the central bulkhead is the differential accumulator. It is essentially a storage battery that is capable of being charged from a number of natural energy sources. We can charge it from the energy banks of our own ship, but this is seldom necessary. In your stratosphere, for example, there are several layers of ionized gas which, although they are rarefied, are also highly charged. By placing the ship in a planetary orbit at this level, it is able to collect, during each orbit, several times the energy required to place it in orbit. It would also, of course, collect a significant number of high-energy electrons from the Sun.

By the term ‘charging the differential accumulator’ I merely mean that a potential difference is created between two poles of the accumulator. The accumulator material has available free electrons in quantities beyond anything of which you could conceive. The control mechanism allows these electrons to flow through various segments of the force rings which you see at the top and bottom of the craft. . . The tremendous surge of electrons through the force rings creates a very strong magnetic field. Since the direction and amplitude of the flow can be controlled through either ring, and in several paths through a single ring, we can create a field which oscillates in a pattern of very precisely controlled modes. In this way we can create magnetic resonance between the two rings or between the several segments of a single ring.

As you know, any magnetic field which is changing in intensity will create an electric field which, at any given instant, is equal in amplitude, opposite in sign and perpendicular to the magnetic field. If the two fields become mutually resonant, a vector force will be generated. Unless the amplitude and the frequency of the resonance are quite high, the vector field will be very small, and may pass unnoticed. However, the amplitude of the vector field increases at a greater rate than the two fields which generate it and, at high resonance levels, becomes very strong. The vector field, whose direction is perpendicular to each of the other two, creates an effect similar to, and in fact identical with, a gravitational field.

If the center of the field coincides with the craft’s center of mass, the only effect will be to increase the inertia, or mass, of the craft. If the center of mass does not coincide with the center of force, the craft will tend to accelerate toward that center. Since the system which creates the field is a part of the ship, it will, of course, move with the ship, and will continue constantly to generate a field whose center of attraction is just ahead of the ship’s center of mass, so that the ship will continue to accelerate as long as the field is generated . . . To slow or stop the craft, the controls are adjusted so that the field is generated with its center just behind the center of mass, so that negative acceleration will result.

Unconventional Communication

‘Incidentally,’ remarked Fry at one point, ‘I don’t even know your name, or do you people not have given names?’

‘We have names, though there is seldom any occasion to use them among ourselves. If I become a member of your race, I shall use the name Alan, which is a common name in your country and is nearly the same as my given name, which is pronounced as though it were spelled “Ah-lahn”.’

Alan said that, whenever it became necessary, Fry would be contacted again, though not necessarily by conventional means. ‘We have recorded your exact frequency pattern,’ he said (a method reported by Albert Coe), and went on briefly to discuss mental telepathy, or ‘extra-sensory perception’:

In the first place, it isn’t extra-sensory at all. It is just as much a part of the body’s normal perception equipment as any of the others, except that during one phase of the development of the race it falls into disuse because it is a rather public form of communication, and during this phase of development the individual requires a considerable degree of privacy in his words and thoughts. Most of your animals use the sense to a greater degree than your people, and for some of your insects, it is the only form of communication . . .

Communication could also be established by means of small, remotely controlled probes, as well as directly, using ‘electronic beam modulation of the auditory nerve’, Alan claimed.

Free Fall

Prior to Alan’s elaborate explanation of propulsion, the craft had flown over New York City – at a reduced height of 20 miles and a reduced velocity of 600 m.p.h., affording Fry an excellent view. ‘The differing temperatures of the various air strata beneath me,’ he wrote, ‘caused the lights to twinkle violently, so that the entire city was a sea of pulsing, shimmering luminescence.’

Before the return trip, Alan offered Fry the chance of experiencing ‘free fall’. ‘To reach this condition fully under the present circumstances would be somewhat dangerous,’ said Alan, ‘but we can approach it closely enough so that while you will still retain some stability, you will experience the sensation of weightlessness.’

‘Instantly the compartment light came on,’ said Fry. ‘While I was attempting to adjust my eyes to the light, my stomach suddenly leaped upward toward my chest.’ Although having been through steep dives and sharp pullouts in aircraft, and ridden in many devices at amusement parks, he had never experienced anything like this.

‘There was no sensation of falling. It simply felt as though my organs, having been released from a heavy strain, were springing upward like elastic bands when released from tension . . . In a few seconds I felt almost normal again.’ Pushing down with his hands on the seat, he then rose slowly to the ceiling, though his body rotated and tipped forward so that he came to rest with his knees on the chair and his eyes only a few inches from the back cushion.

Planetary Independence

Fry was rather shocked to notice a very earthly symbol imprinted on the material of his seat. It was that of the tree and the serpent – the caduceus. ‘It is found, in one form or another, in the legends, the inscriptions and the carvings of virtually every one of our early races,’ he said. ‘It has always seemed to me a peculiarly earthly symbol, and it was startling to see it appear from the depths of space, or from whatever planet you call home.’ Alan responded:

It is difficult even to outline, in a few minutes of discussion, the events of many centuries. For it has been centuries since we have called any planet home. The space ships upon which we live, and work and learn, have been our only home for generations. Like all space-dwelling races, we are now essentially independent of planets. Some of our craft are very large, judged by your standards, since they are many times larger than your largest ships. We have no personal need to approach or land upon any planet, except occasionally to obtain raw materials for new construction, and that we usually obtain from asteroids or uninhabited satellites [moons].

Our ships are closed systems. That is, all matter within the craft remains there; nothing is emitted, ejected or lost from it. We have learned simple methods of reducing all compounds to their elements, and for recombining them in any form . . . For example, we breathe in the same manner as you do. That is, our lungs take in oxygen from the air, and some of that oxygen is converted to carbon-dioxide in the body processes. Therefore, the air in our ship is constantly passed through solutions which contain plant-like organisms which absorb carbon-dioxide, use the carbon in their own growth, and return the oxygen to the air. Eventually those plants become one of our foods . . .

It may be difficult for you to conceive of a race of intelligent beings who spend all of their lives within the relatively restricted confines of a space ship. You may even be inclined to feel pity for such a race. We, on the other hand, are inclined to feel pity for the relatively primitive races which are still confined to the surface of a single planet, where they are unable to control . . . earthquakes, floods, tornadoes, tidal waves, blizzards, drought, and a dozen other hazards . . .

While our bodies seldom leave the ship, our technology has provided us with almost unlimited extensions of our senses so that . . . we can be intimately present at any time and at any place which we may choose, providing that the place is within a few thousand miles of our ship. Through a portion of our technology which your race has not yet begun to acquire, we are able to generate and apply simple forces at points quite remote from our craft. Our abilities may be somewhat startling and incredible to some of your people but they are not actually as startling and incredible as the scientific knowledge and abilities your people now have, compared to those which your ancestors possessed a few hundred years ago . . .

A Common Ancestry

Alan explained that the symbol of the tree and the serpent was not unique to Earth. It is a natural one, ‘perhaps because life is said to originate in the waters of a planet, and the undulations of a serpent are a convenient symbol for the waves of a sea. The tree is almost always the symbol of life, beginning in the sea, rising to the atmosphere, and finally into space.’ But there was another factor, he added, that perhaps was significant.

Your people, and some of mine, including myself, have, at least in part, a common ancestry. Tens of thousands of years ago, some of our ancestors lived upon this planet, Earth. There was, at that time, a small continent in a part of the now sea-covered area which you have named the Pacific Ocean. Some of your ancient legends refer to this sunken land mass as the ‘Lost Continent of Lemuria, or Mu’.

Our ancestors had built a great empire and a mighty science upon this continent. At the same time, there was another rapidly developing race upon a land mass in the south-west portion of the present Atlantic Ocean. In your legends, this continent has been named Atlantis. There was rivalry between the two cultures, in their material and technological progress. It was friendly at first, but became bitter. . . In a few centuries their science had passed the point which your race has reached. Not content with releasing a few crumbs of the binding energy of the atom, as your science is now doing, they had learned to rotate entire masses upon the energy axis. Energies equal to 75 million of your kilowatt hours were released by the conversion of a bit of matter about the mass of one of your copper pennies.

With the increasing bitterness between the two races . . . it was inevitable that they would eventually destroy each other. The energies released in that destruction were beyond all human imagination. They were sufficient to cause major shifts in the surface configuration of the planet, and the resulting nuclear radiation was so intense and so widespread that the entire surface became virtually unfit for habitation, for a number of generations.

Return To Earth

Alan told Fry that further discussion had to await another meeting, as time was up and they had landed back at White Sands. ‘It is on the ground now, and I will open the door,’ he said. ‘We will wait until you are a little distance from the craft before we retrieve it . . . Take care of yourself until we return.’

Dazed after such a fantastic experience, Fry stepped down and stumbled several paces through the sand before turning to look at the craft.

The door had closed behind me and, as I turned, a horizontal band of orange-colored light appeared about the central, or widest part of the ship, and it leaped upward as though it had been released from a catapult. The air rushing in to replace that which had been displaced upward impelled me a full step forward and almost caused me to lose my balance. I managed to keep my eyes on the craft while the band of light went through the colors of the spectrum from orange to violet. As the light went through the violet band, the craft had risen several thousands of feet in the air, and I could follow it no longer.

Fry then became thoroughly depressed. It was as if his life’s work had lost all significance. ‘A few hours before, I had been a rather self-satisfied engineer, setting up instruments for the testing of one of the largest rocket motors in existence. While I realized that my part in the project was a small one, I felt that, through my work, I was traveling in the forefront of progress. Now I knew that rocket motors . . . had been obsolete for thousands of years. I felt like a small and insignificant cog in a clumsy and backward science, which was moving toward its own destruction.’

Fry did not report or mention his experience to anyone, partly because he had tacitly given his agreement to Alan not to do so, and also because he was convinced no one would believe him. He continued rather unenthusiastically with his work, testing various types and sizes of rocket motor. Alan had said he would return in a few months, and Fry grew restless. After the first series of tests were completed, he went back home to California, then returned to the base for a second series of tests.

One evening, after Fry had driven from his quarters at the ‘H’ building to the test site’s instrument room, he saw an unusual glowing object, about a foot in diameter. Walking towards it, he suddenly heard Alan’s voice, as if beside him. ‘Yes, Dan, it’s ours. Since we are not using the sampling craft now, we thought it best to send down a small communications amplifier. We could get along without it, but it does [reduce] the chance of error in our communications almost to zero.’ After allowing Fry to calm down following the shock, Alan went on to explain that he would eventually be able to successfully adapt his body to Earth’s environment, but that he would need help.

‘If you do not wish to assist us,’ he continued, ‘all memory of this meeting and the previous one will be erased from your mind . . . If, on the other hand, you do decide to assist us, you may find yourself in a situation that is not easy to endure . . . The only reward we can promise you is the inward satisfaction of having assisted in the survival of your race, and the acquisition of considerable knowledge and understanding that you would not otherwise be able to gain.’ Fry gave his consent.

Alan first asked Fry to gather a number of textbooks dealing with the English language and mathematics. Regarding the latter, Alan explained that his system was based on multiples of 12, rather than 10, and that it would take him a while to master the ‘new’ system. These textbooks, he said, should be placed on a certain ledge at the test stand, where they would be ‘collected’ by a small sampling device, then analyzed, copied, and returned 24 hours later. The arrangement worked well. On several occasions, Fry obtained books (including the Bible) for Alan from the base library, and on each occasion they were returned safely.

Excerpt from Alien Base

See Part II here.

Posted in Life On Other Worlds, Other Topics, UFOswith comments disabled.